Hi everyone,

I hope all of you had an enjoyable holiday. I spent my week off from work spending time with the family and catching up on some reading. One area I decided to spend some time reading up on is Microsoft’s Cloud App Security. For those unfamiliar with the solution, it’s Microsoft’s entry into the cloud access security broker (CASB) (or Cloud Security Gateway (CSG) if you’re a Forrester reader) market. If you haven’t heard of “CASB” or “CSG”, don’t worry too much. While the terminology is new, many of the collection of technologies encompassing a typical CASB or CSG are not new, simply used together in new and creative ways. For a quick intro, take a read through this article and follow up with some Forrester and Gartner research for a deeper dive.

Since I haven’t had much experience with a product specifically marketing itself as a CASB, I thought it would be a great opportunity to play around with Microsoft’s solution. A good first step for any organization to grasp the value of a CASB is to explore what’s happening within the organization outside the view of IT, or as the marketers love to call it, shadow IT. The ease of consuming cloud technologies such as software as a service (SaaS) applications has been both a blessing and a curse. The new technology has been wonderful in cutting IT costs, bringing the technology closer to the business, providing for shorter time to market for new features, and providing simpler integration paths for different applications and services. On the negative side, the ease of use of these solutions means an average employee is using far more of them than is officially sanctioned by IT. This can lead to issues like loss of critical data, non-compliance with policy, or multiple business groups within an organization subscribing to the same service resulting in redundant licensing costs.

Wouldn’t it be great to get visibility into that shadow IT? Since a majority of cloud solutions work over standard HTTP(S) the services are readily accessible to the user without the user having to request additional ports be opened on the firewall. This means it’s much more challenging to track who is using what and what they’re doing with those services. Many organizations attempt to control these types of solutions with a traditional forward web proxy. However, too much focus is put on blocking the “bad” sites instead of analyzing the overall patterns of usage of services. Microsoft’s Azure AD Cloud Discovery is a feature of Azure Active Directory that can be used in conjunction with Cloud App Security’s catalog of app to provide visibility into what’s being accessed as well as providing information as to the risks the services being accessed present to the organization.

To simulate a typical medium to large organization and get some good testing done with Cloud App Discovery, I’m going to add a forward web proxy to my home lab. As I’ve mentioned in previous blog entries I have a small form factor computer running pfsense which I use as my lab networking security appliance. Out of the box, it supports a base install of Squid which can be added and configured to act as a forward web proxy with minimal effort. It gets a bit more challenging when you want to add authentication to the proxy because the built-in options for the pfsense implementation are limited to local, LDAP, and RADIUS authentication. I want authentication so I can identify users connecting to the proxy and associate the web connections with specific users but I want to use Kerberos so I get that seamless single sign on experience.

Like many open source products, the documentation on how to setup Squid running on pfsense and using Kerberos authentication is pretty terrible. Searching the all-powerful Google presents lots of forum posts with people asking how to do it, pieces of answers that don’t make much sense, and some Wikis on how to configure Squid to use Kerberos on a standard server. Given the lack of good documentation, I thought it would be fun to work my way through it and compile a walkthrough. I’m issuing the standard disclaimer that this is intended for lab purposes only. If you’re trying to deploy pfsense and Squid in a production environment, do more reading and spend time doing it safely and securely.

I won’t be covering the basic setup of pfsense as there are plenty of guides out there and the process is simple for anyone with any experience in the network appliance realm. For this demonstration I’ll be running a box with pfsense 2.4.2 installed.

On to the walkthrough!

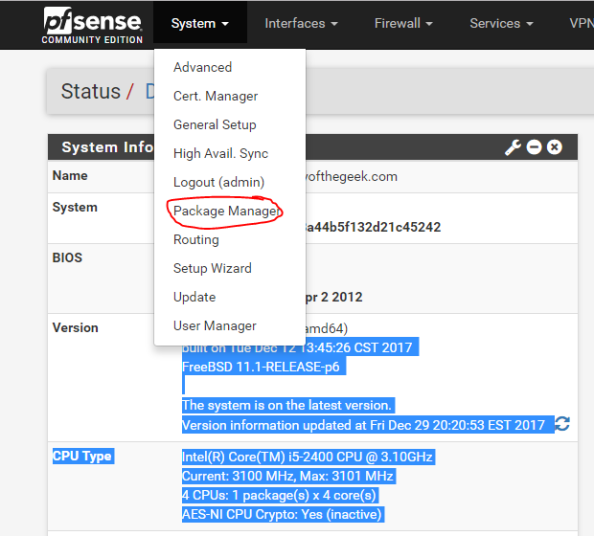

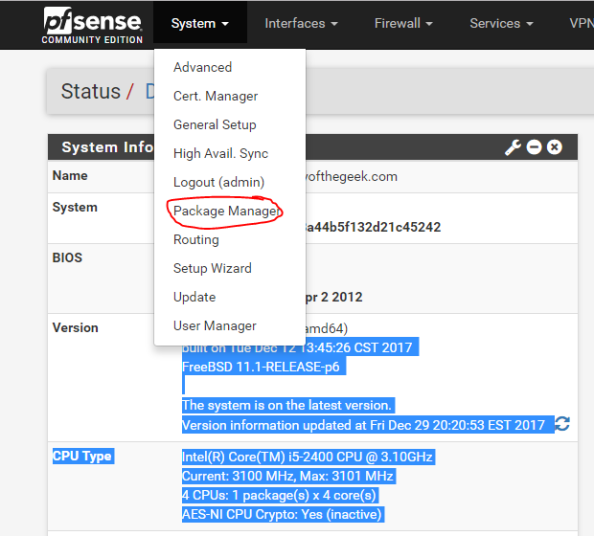

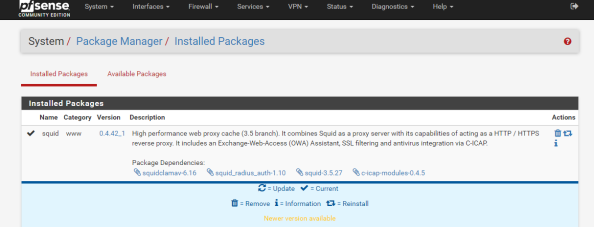

The first step in the process is to add the Squid package through the pfsense package manager UI.

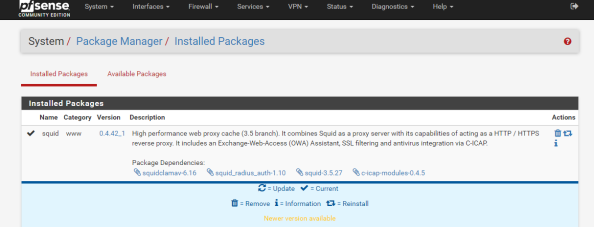

On the Package Manager screen, select the Available Packages section and install the Squid package. After the installation is complete, you’ll see Squid shown in the Installed Packages section.

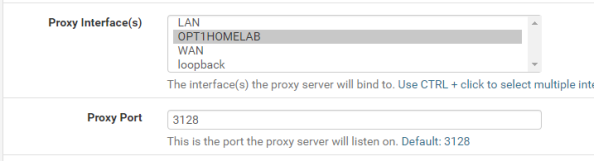

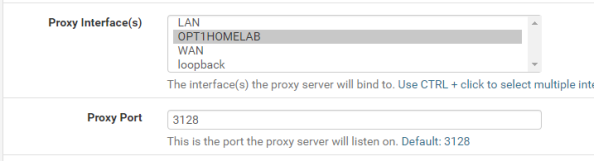

Notice the package installed is a branch of the 3.5 release while the latest release available directly via Squid is 4.0. It’s always fun to have the latest and greatest, but pfsense is an all-in-one solution so it comes with some sacrifices. Let’s get some of the basic configuration settings done with. Go to the Services menu, select the Squid Proxy Server menu item, and go the General section. First up choose the interface you want Squid to be available for and specify a port for it to listen on.

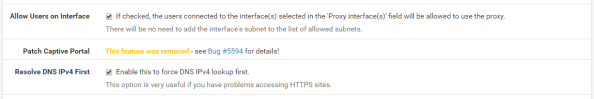

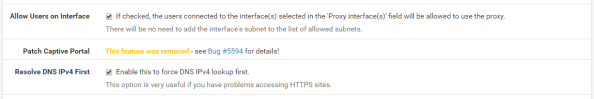

Now check off the Allow Users on Interface unless you have a reason to limit it to certain subnets attached to the interface. Additionally I’d recommend checking the Resolve DNS IPv4 First option. I banged my head against the wall with a ton of issues with Squid when I turned on authentication and this option wasn’t set. You can thank me for saving you hours of Google and trying other options.

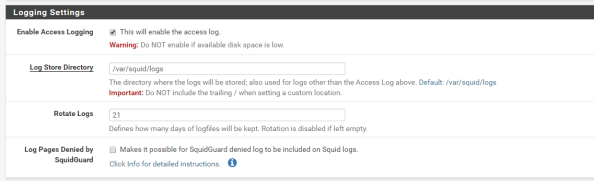

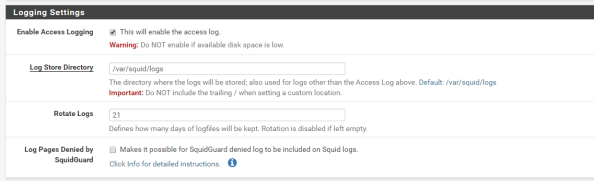

Setup basic logging with the settings below.

Basic settings are complete and it’s a good time to test the proxy from a client machine to verify its base functionality. You can do this by directing one of your client machines to use the proxy and attempting to access a website.

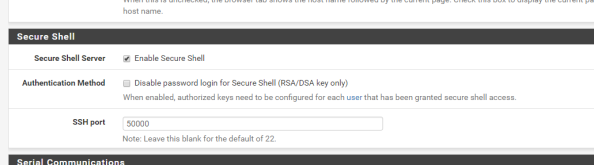

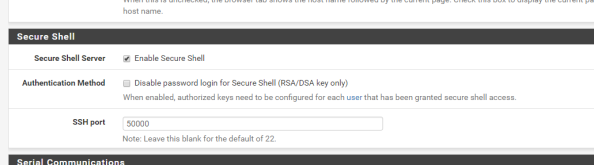

After you have verified functionality you’ll need to add support for SSH to the pfsense box since we’ll need to make some changes via the command shell. For that you’ll want to navigate the System menu, select the Advanced menu item, and go to the Admin Access section. Scroll down from there to the Secure Shell section and click the checkbox for Enable Secure Shell and set a the SSH port to the port of your choice. I chose 50,000.

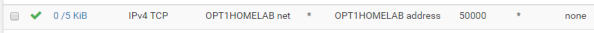

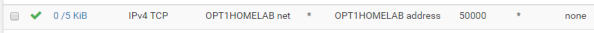

The Secure Shell Server is active, but the firewall blocks access to it across all interfaces by default. You now need to create the appropriate firewall rule to allow access from devices behind the interface you wish to use to SSH to the box. For me this is the interface that my lab devices connect to. For this you’ll select Firewall from the top menu, select the Rules menu item, and select the appropriate interface from the menu items. Once there, click the Add button to create a firewall rule allowing devices within the subnet to hit the router interface over the port you configured earlier as seen below. The SSH listener will now be running and will be accessible from the designated interface.

Now you must configure DNS such that the pfsense box can resolve the Active Directory DNS namespace to perform Kerberos related activities. You can go the easy route and make the Active Directory domain controller the primary DNS server for pfsense via the GUI. However, I use pfsense as the primary DNS resolver for the lab environment and forward queries to Google’s DNS servers at 8.8.8.8.

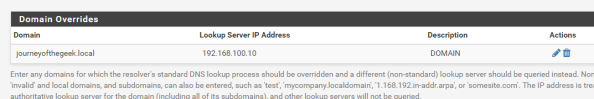

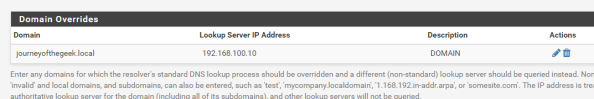

In order to continue using with my preferred configuration, I needed to take a few additional steps. First I needed to add a Domain Override to the DNS Resolver service on pfsense to ensure it doesn’t pass the query along to the external DNS server. I did this by selecting Services from the main menu, selecting the DNS Resolver menu item, and going to the General Settings section. I then scrolled down to the Domain Overrides section and added the appropriate override for my Active Directory DNS namespace as seen below. Take note that you can’t go modifying the resolv.conf as you would in a normal Linux distro since pfsense will scrub any changes you make to the file each time it restarts its services. Get used to this behavior, we’re going to see it a number of times through this blog entry and we’ll have to learn to work around that limitation (feature?).

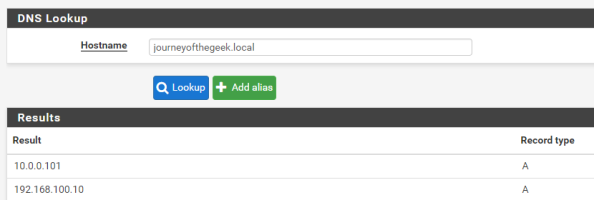

Next up you’ll want to verify name resolution is working as intended and it can be tested by running a query from the pfsense box. Go to the Diagnostics on the main menu, select the DNS Lookup item, and type in the hostname representing the Active Directory DNS namespace. It should resolve to the entries representing domain controllers in your Active Directory domain. Successful testing makes the DNS configuration complete.

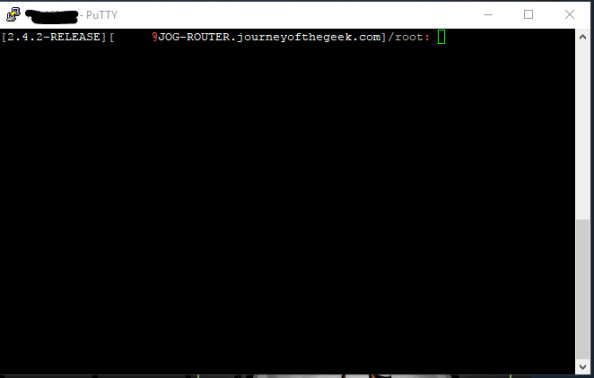

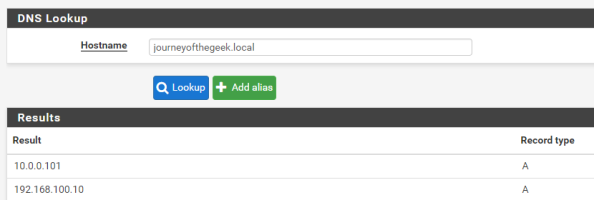

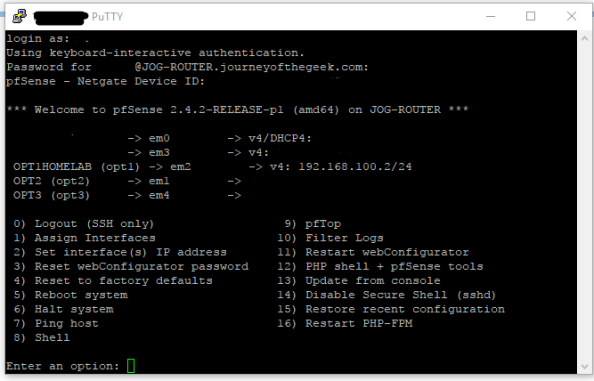

On to the guts of the configuration. Pfsense comes with the krb5 package installed so all you need to do is configure it. For that you are going to need to access the command shell. Open up your favorite SSH client and connect to the pfsense box as an administrative user. Upon successful login you’ll see the menu below.

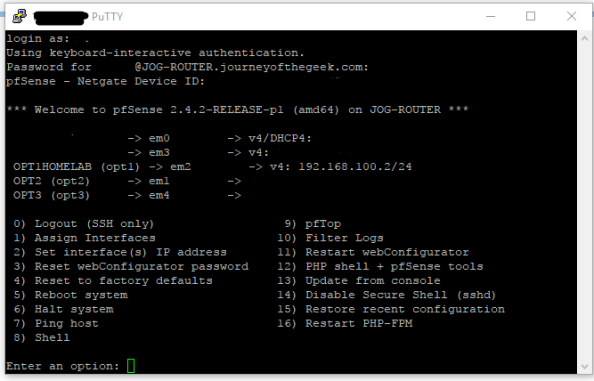

You want to hit the command shell so choose option 8 and you will be dropped into the shell.

You want to hit the command shell so choose option 8 and you will be dropped into the shell.

The first step is to configure the krb5 package to integrate with the Active Directory domain. For that you’ll need to create a krb5.conf file. Create a new a krb5.conf file in the /etc/ directory and populate it with the appropriate information. I’ve included the content of my krb5.conf file as an example.

[libdefaults]

default_realm = JOURNEYOFTHEGEEK.LOCAL

dns_lookup_realm = false

dns_lookup_kdc = true

default_tgs_enctypes = aes128-cts-hmac-sha1-96

default_tkt_enctypes = aes128-cts-hmac-sha1-96

permitted_enctypes = aes128-cts-hmac-sha1-96

[realms]

JOURNEYOFTHEGEEK.LOCAL = {

kdc = jog-dc.journeyofthegeek.local

}

[domain_realm]

.journeyofthegeek.local = JOURNEYOFTHEGEEK.LOCAL

journeyofthegeek.local = JOURNEYOFTHEGEEK.LOCAL

[logging]

kdc = FILE:/var/log/kdc.log

Default = FILE:/var/log/krb5lib.log

Check out the MIT documentation on the options available to you in the krb5.conf. I made the choice to limit the encryption algorithms to AES128 for simplicity purposes, feel free to use something else if you wish. Once the settings are populated the file can be saved.

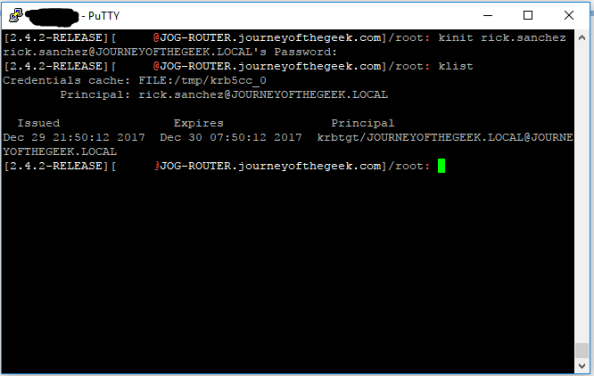

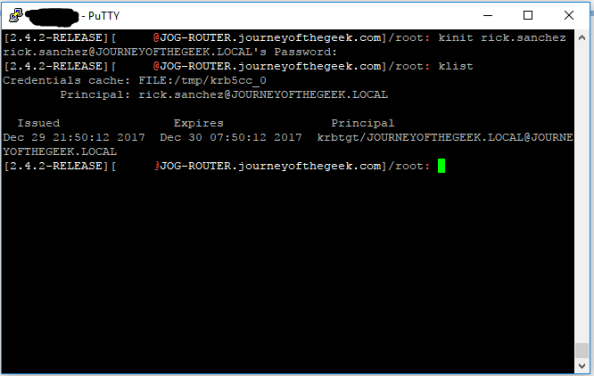

It’s time to test the Kerberos configuration. You do that by using running kinit and authenticating as a valid user in the Active Directory domain. If the configuration is correct klist will display the a valid Kerberos ticket granting ticket (TGT) for the user.

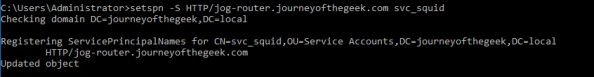

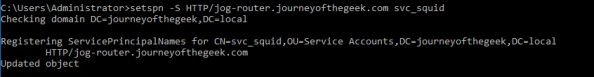

The system is now configured to interact with the Active Directory domain using Kerberos. You now need to create a security principal in Active Directory to represent the Squid service. Create a new user in Active Directory and name it whatever you wish, I used svc_squid for this lab. Since I chose to use AES128, I had to select the account control option on the user account in Active Directory Users and Computers (ADUC) that the service supported AES128. You can ignore that step if you chose not to force an encryption level. Now a service principal name (SPN) for the service is needed to identify the service when a user attempts to authenticate to it. For that you’ll need to open an elevated command prompt and use the setspn command.

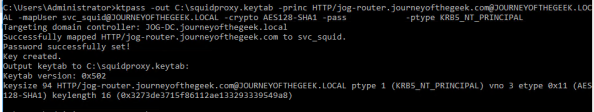

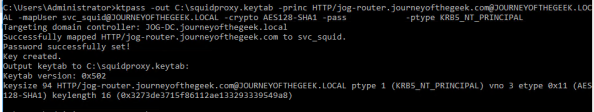

Wonderful you have a security principal created and it includes the appropriate identifier. You now need to create a keytab that the service can use to authenticate to Active Directory. In comes ktpass. From the same elevated command prompt run the command as seen below.

Pay attention to case sensitivity because it matters when we’re talking MIT Kerberos, which is Kerberos implementation pfsense is using. The link I included above will explain the options. I set the crypto option to AES128 to ensure the keytab aligns with the other options I’ve configured around encryption.

Next up you need to transfer the keytab to the pfsense box. I used WinSCP to transfer the keytab to the pfsense box to the /usr/local/etc/squid/ directory. The keytab is on the pfsense box but you need to tell Squid where the keytab is. In a typical Squid implementation you’d define variable in the Squid startup script which would be consumed by the authentication helper. However, this is another case where pfsense will overwrite any changes you make to the startup script.

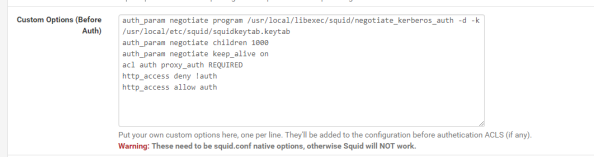

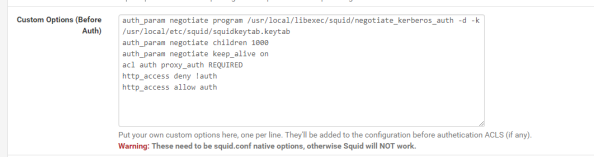

In addition to being unable to modify the startup script to set, pfsense also overwrites any changes you make directly to the squid.conf file. To get around this you’ll need to add the configuration options to the config file through the pfsense GUI. From within the GUI go to the Services section of the main menu, select the Squid Proxy Server menu item, go to the General section, scroll down and hit the Advanced Options button and scroll to the Advanced Features section. In the Custom Options (Before Auth) field, you’ll want to add the lines below.

The first four lines I’ve added here are called directives in Squid. The first directive instructs Squid to use the negotiate_kerberos_auth authentication helper. The options I’ve added to the helper set a few different configuration options for the helper. The -k option allows me to direct Squid to the keytab file I added to the server which I couldn’t do with a variable in the startup script. The -d option writes debug information for the helper to Squid cache.log and the -t option shuts off the replay cache for MIT Kerberos. The second directive sets the child authentication processes to 1,000. You’ll want to do some research on this directive if you’re moving this into a production environment. I simply choose 1000 so I wouldn’t run any risk of getting my authentication requests queued for the purposes of this lab. The third directive is set to on by default and should only be set to off if you run into issues with PUT/POST requests.

The fourth directive starts enforcing access controls within Squid. Access controls within Squid are a bit weird. The Squid wiki does a decent job of explaining how they work. The short of what I’ve done in the fourth directive is create an access list called auth which will contain all users who successfully authenticate against Squid. The next line denies users access to the http_access list if the user doesn’t below to the auth access line (blocking non-authenticated users). The final line allows users who are in the auth list into the http_access list (allows authenticated users).

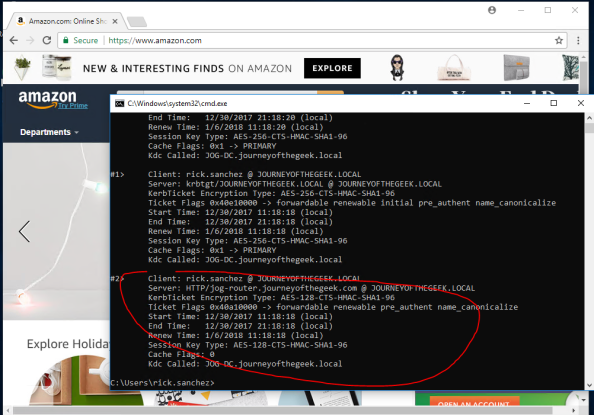

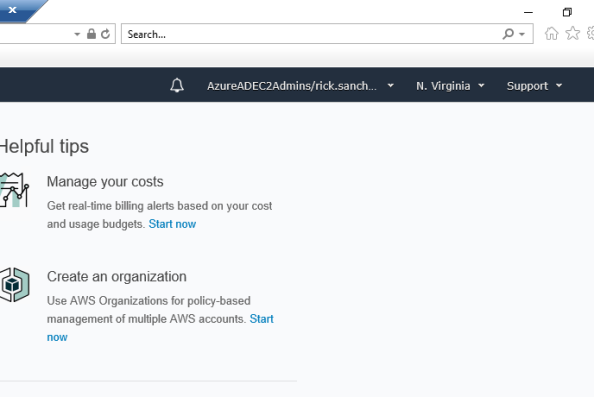

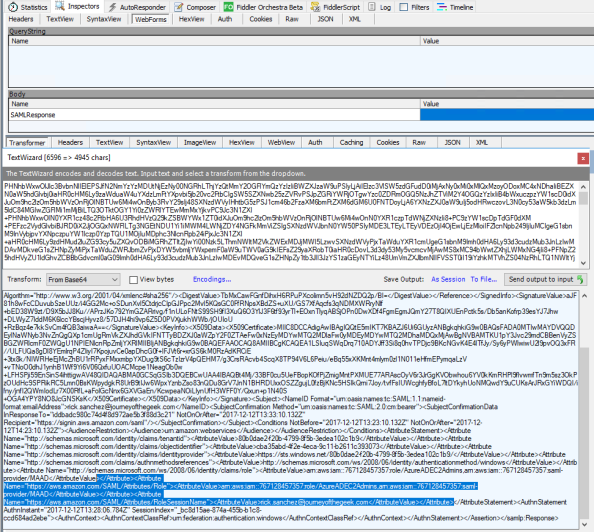

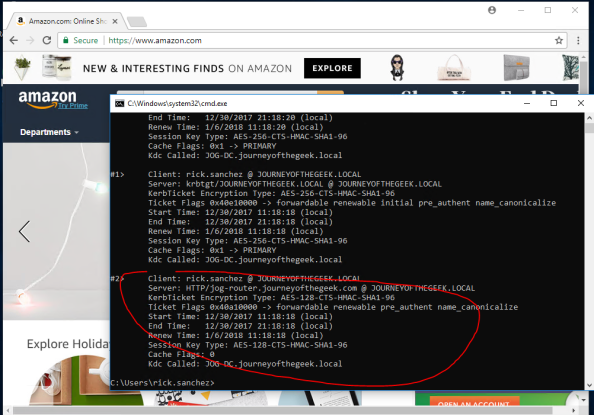

With that last amount of configuration, you’ve gotten pfsense and Squid configured for Kerberos authentication. I’ll quickly demonstrate the what a successful implementation looks like. For that I’m going to bounce over to a Windows 10 domain-joined machine with Chrome installed and configured to use the proxy server. Navigating to Amazon displays the webpage with no authentication prompts and running a klist from a command prompt shows I have a Kerberos ticket for the proxy.

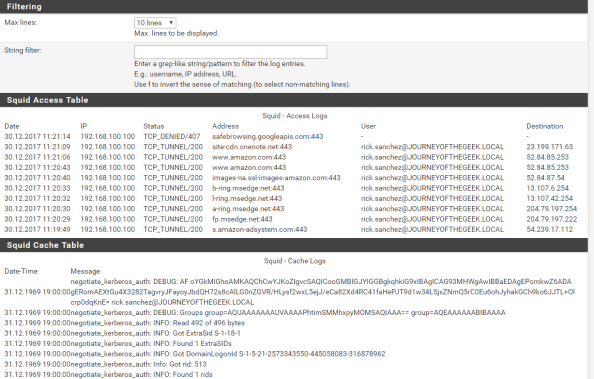

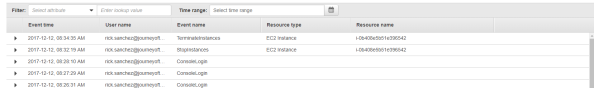

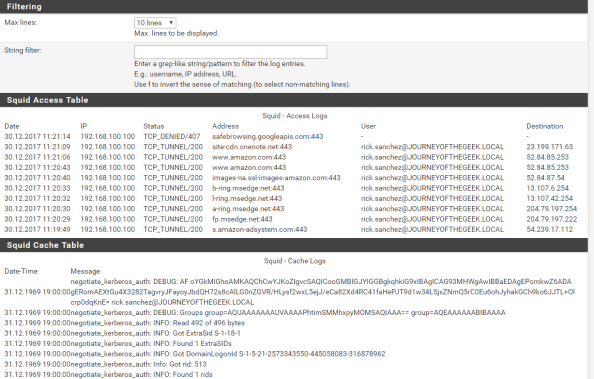

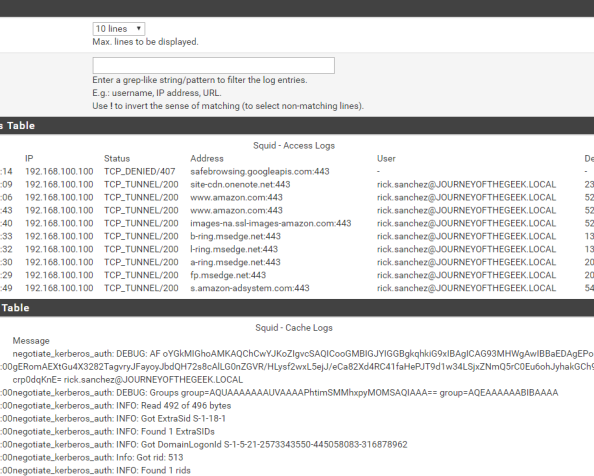

Going back into the pfsense GUI, going to the Services menu, selecting the Squid Proxy Server menu item and navigating to the Real Time section shows the access log displaying Rick Sanchez accessing Amazon and successful consumption of the Kerberos ticket in the Cache Log section.

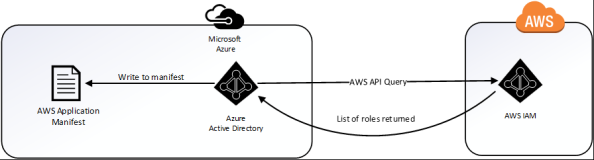

In a future post I’ll dig a bit deeper into Azure AD Cloud Discovery and setup automatic forwarding of logs using the Microsoft collector.

Have a happy New Year!

You want to hit the command shell so choose option 8 and you will be dropped into the shell.

You want to hit the command shell so choose option 8 and you will be dropped into the shell.