Welcome back fellow geeks. Today I’m going to be looking at a brand new capability Microsoft announced entered public preview this week. With the introduction of Hybrid Azure Active Directory Password Protection Microsoft continues to extend the protection it has based into its Identity-as-a-Service (IDaaS) offering Azure Active Directory (AAD).

If you’ve administered Windows Active Directory (AD) in an environment with a high security posture, you’re very familiar with the challenges of ensuring the use of “good” passwords. In the on-premises world we’ve typically used the classic Password Policies that come out of the box with AD which provide the bare minimum. Some of you may even have leveraged third-party password filters to restrict the usage of commonly used passwords such as the classic “P@$$w0rd”. While the third-party add-ins filled a gap they also introduce additional operational complexity (Ever tried to troubleshoot a misbehaving password filter? Not fun) and compatibility issues. Additionally the filters that block “bad” passwords tend to use a static data set or a data set that has to be manually updated and distributed.

In comes Microsoft’s Hybrid Azure Active Directory Password Protection to save the day. Here we have a solution that comes directly from the vendor (no more third-party nightmares) that uses the power of telemetry and security data collected from Microsoft’s cloud to block the use of some of the most commonly used passwords (extending that even further with the use of fuzzy logic) as well as custom passwords you can provide to the service yourself. In a refreshing turn of events, Microsoft has finally stepped back from the insanity (yes I’m sorry it’s insanity for most organizations) of requiring Internet access on your domain controllers.

After I finished reading the announcement this week I was immediately interested in taking a peek behind the curtains on how the solution worked. Custom password filters have been around for a long time, so I’m not going to focus on that piece of the solution. Instead I’m going to look more closely at two areas, deployment and operation of the solution. Since I hate re-creating existing documentation (and let’s face it, I’m not going to do it nearly as well as those who do it for a living) I’ll be referencing back to Microsoft documentation heavily during this post so get your dual monitors powered up.

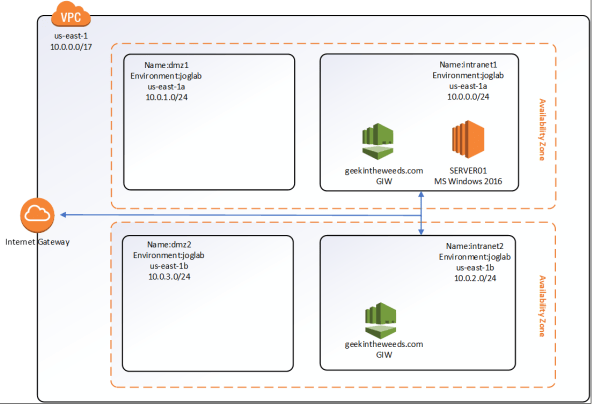

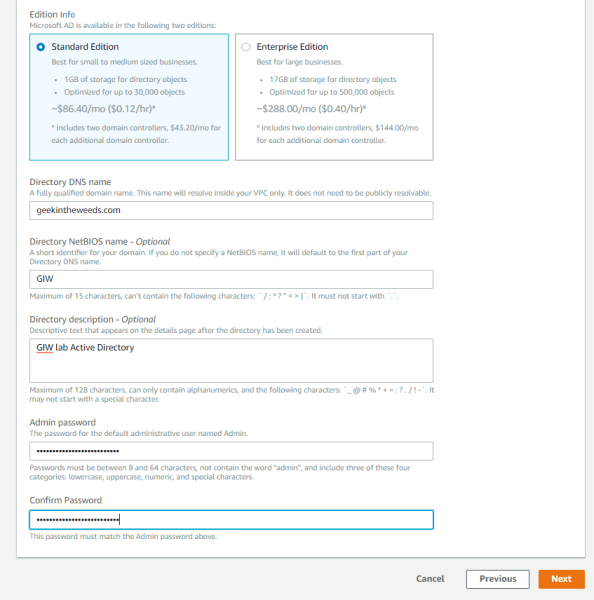

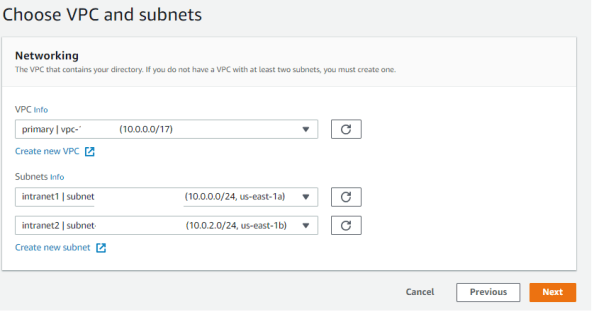

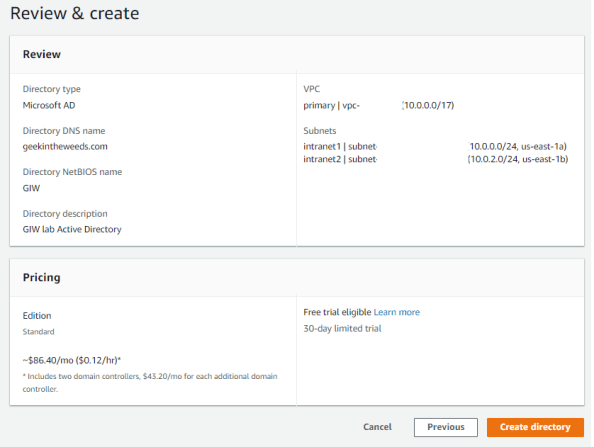

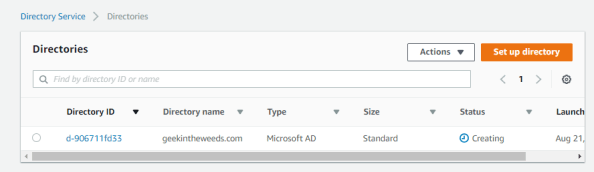

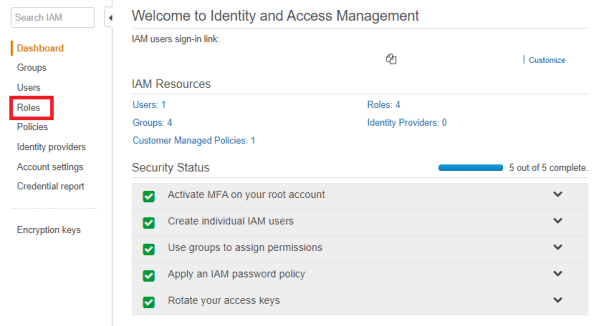

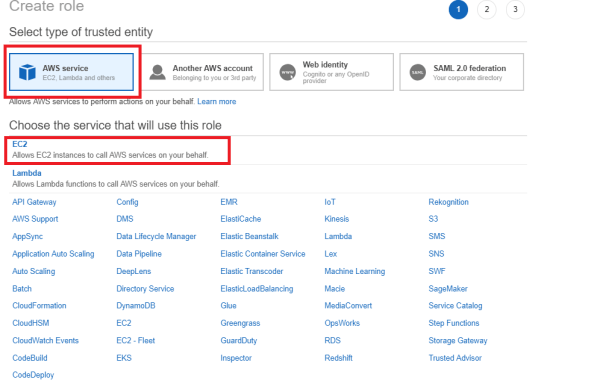

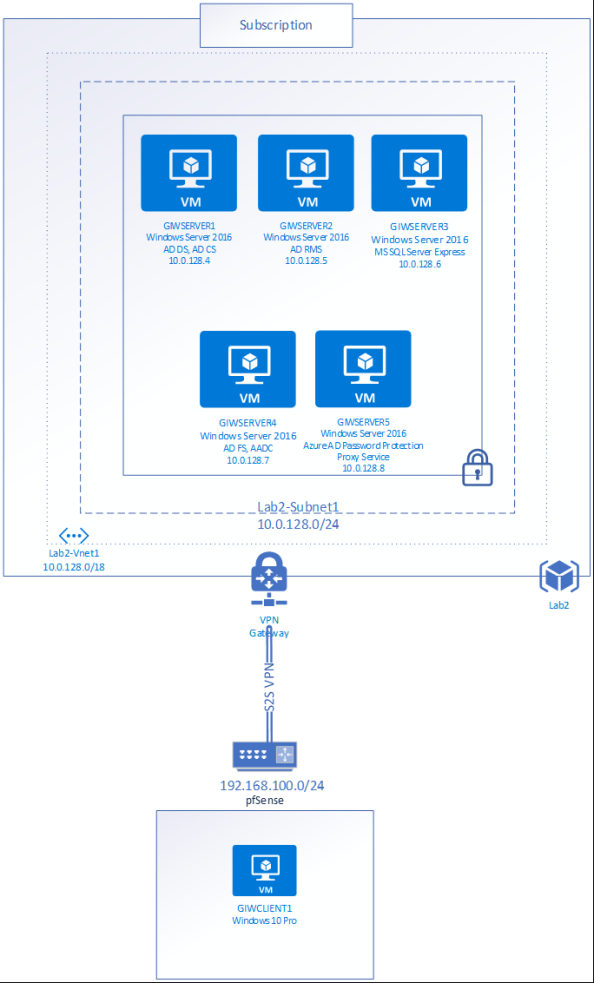

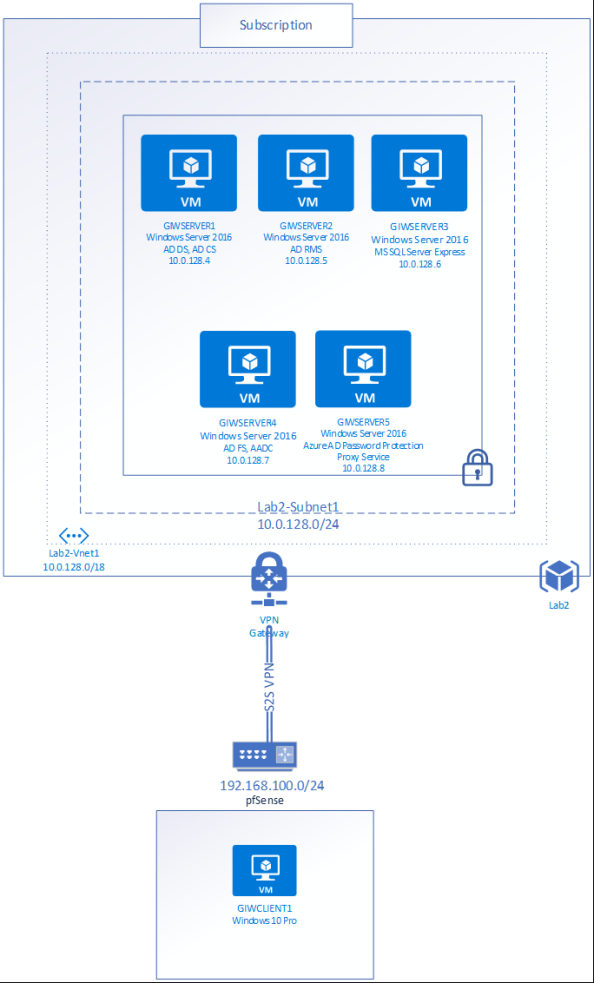

I’ll be using my Geek In The Weeds tenant for this demonstration. The tenant is synchronized and federated with AAD with Azure Active Directory Connect (AADC) and Active Directory Federation Services (AD FS). The tenant is equipped with some Office 365 E5 and Enterprise Mobility+Security E5 licenses. Since I’ll need some Windows Servers for this, I’ll be using the lab seen in the diagram below.

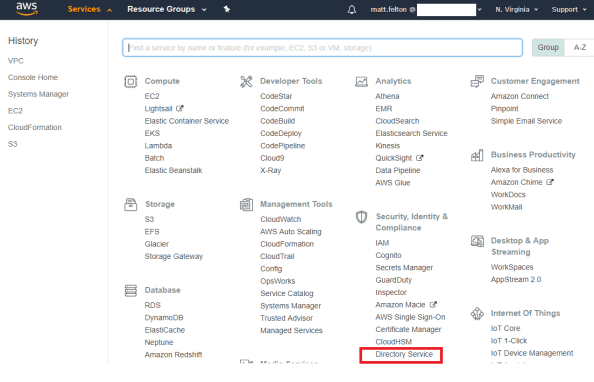

The first thing I needed to do was verify that my AAD tenant was configured for Azure Active Directory Password Protection. For that I logged into the portal as a global administrator and selected the Azure Active Directory blade. Scrolling down to the Security section of the menu shows an option named Authentication Methods.

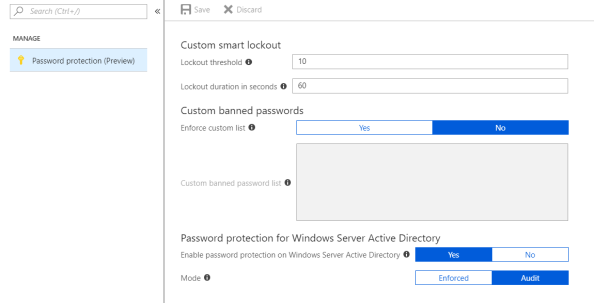

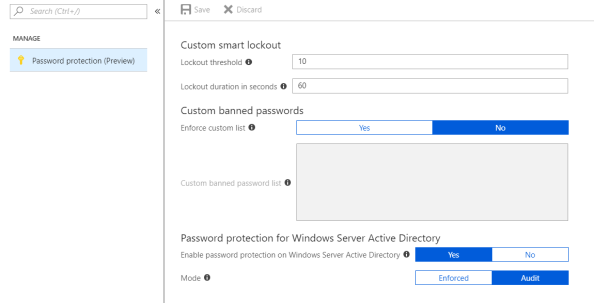

After selecting the option a new blade opens with only one menu item, Password Protection. Since it’s the option there, it opens right up. Here we can see the configuration options available for Azure Active Directory Password Protection and Smart Lockout. Smart Lockout is at this time a feature specific to AAD so I’m not going to cover it. You can read more about that feature in the Microsoft announcement. The three options that we’re interested in for this post are within the Custom Banned Passwords and Password protection for Windows Server Active Directory.

The custom banned passwords section allows organizations to add additional blocked passwords beyond the ones Microsoft provides. This is helpful if organizations have a good grasp on their user’s behavior and have some common words they want to block to keep users from creating passwords using those words. Right now it’s limited to 1000 words with one word per line. You can copy and paste from a another document as long as what you paste is a single word per line.

I’d like to see Microsoft lift the cap of 1000 words as well as allowing for programmatic updating of this list. I can see some real cool opportunities if this is combined with telemetry obtained from on-premises. Let’s say the organization has some publicly facing endpoints that use a username and password for authentication. That organization could capture the passwords used during password spray and brute force attacks, record the number of instances of their use, and add them to this list as the number of instances of those passwords reach certain thresholds. Yes, I’m aware Microsoft is doing practically the same thing (but better) in Azure AD, but not everything within an organization uses Azure AD for authentication. I’d like to see Microsoft allow for programmatic updates to this list to allow for such a use case.

Let’s enter two terms in the custom banned password list for this demonstration. Let’s use geekintheweeds and journeyofthegeek. We’ll do some testing later to see if the fuzzy matching capabilities extend to the custom banned list.

Next up we configuration options have Password protection for Windows Server Active Directory. This is will be my focus. Notice that the Enable password protection on Windows Server Active Directory option is set to Yes by default. This option is going to control whether or not I can register the Azure AD Password Protection proxy service to Azure AD as you’ll see later in the post. For now let’s set to that to No because it’s always interesting to see how things fail.

I’m going to leave Mode option at Audit for now. This is Microsoft’s recommendation out of the gates. It will give you time to get a handle on user behavior to determine how disruptive this will be to the user experience, give you an idea as to how big of a security issue this is for your organization, as well as giving you an idea as to the scope of communication and education you’ll need to do within your organization.

There are two components we’ll need to install within on-premises infrastructure. On the domain controllers we’ll be installing the Azure AD Password Protection DC Agent Service and the DC Agent Password Filter dynamic-link library (DLL). On the member server we’ll be installing the Azure AD Password Protection Proxy Service. The Microsoft documentation explains what these two services do at a high level. In short, the DC Agent Password Filter functions like any other password filter and captures the clear text password as it is being changed. It sends the password to the DC Agent Service which validates the password according to the locally cached copy of password policy that it has gotten from Azure AD. The DC Agent Service also makes requests for new copies of the password policy by sending the request to the Proxy Service running on the member server which reaches out to Azure AD on the Agent Service’s behalf. The new policies are stored in the SYSVOL folder so all domain controllers have access to them. I sourced this diagram directly from Microsoft, so full credit goes to the product team for producing a wonderful visual representation of the process.

The necessary installation files are sourced from the Microsoft Download Center. After downloading the two files I distributed the DC Agent to my sole domain controller and the Proxy Service file to the member server.

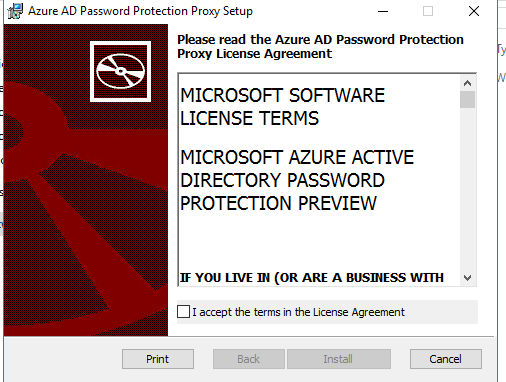

Per Microsoft instructions we’ll be installing the Proxy Service first. I’d recommend installing multiple instances of the Proxy Service in a production environment to provide for failover. During the public preview stage you can deploy a maximum of two proxy agents.

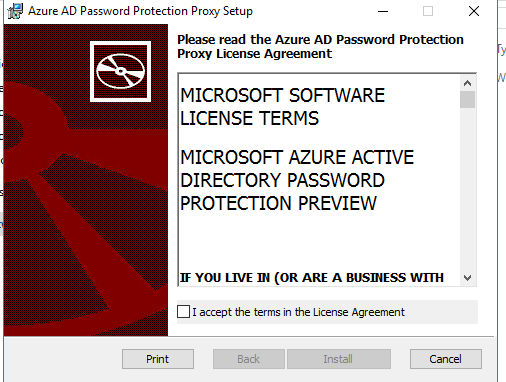

The agent installation could be pushed by your favorite management tool if you so choose. For the purposes of the blog I’ll be installing it manually. Double-clicking the MSI file initiates the installation as seen below.

The installation takes under a minute and then we receive confirmation the installation was successful.

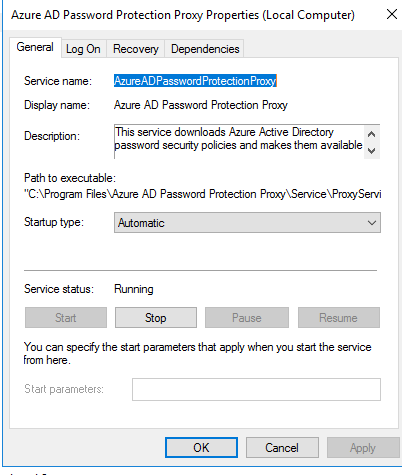

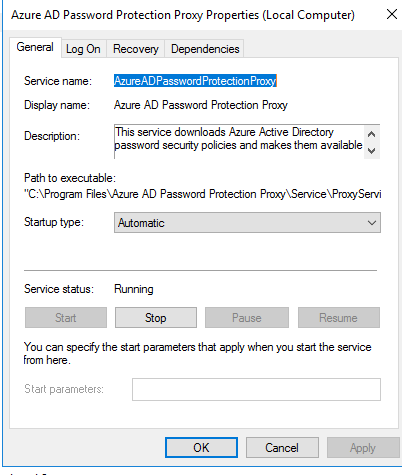

Opening up the Services Microsoft Management Console (MMC) shows the new service having been registered and that it is running. The service runs as Local System.

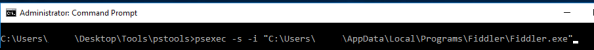

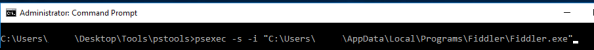

Before I proceed further with the installation I’m going to startup Fiddler under the Local System security context using PSEXEC. For that we open an elevated command prompt and run the command below. The -s parameter opens the application under the LOCAL SYSTEM user context and the -i parameter makes the window interactive.

Additionally we’ll setup another instance of Fiddler that will run under the user’s security context that will be performing the PowerShell cmdlets below. When running multiple instances of Fiddler different ports needs to be used so agree to the default port suggested by Fiddler and proceed.

Now we need to configure the agent. To do that we’ll use the PowerShell module that is installed when the proxy agent is installed. We’ll use a cmdlet from the module to register the proxy with Azure Active Directory. We’ll need a non-MFA enforced (public preview doesn’t support MFA-enforced global admins for registration) global admin account for this. The account running the command also needs to be a domain administrator in the Active Directory domain (we’ll see why in a few minutes).

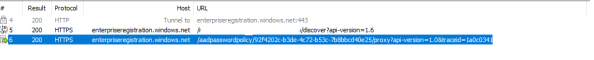

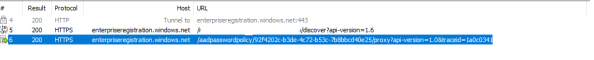

The cmdlet successfully runs. This tells us the Enable password protection on Windows Server Active Directory option doesn’t prevent registration of the proxy service. If we bounce back to the Fiddler capture we can see a few different web transactions.

First we see a non-authenticated HTTP GET sent to https://enterpriseregistration.windows.net/geekintheweeds.com/discover?api-version=1.6. For those of you familiar with device registration, this endpoint will be familiar. The endpoint returns a JSON response with a variety of endpoint information. The data we care about is seen in the screenshot below. I’m not going to bother hiding any of it since it’s a publicly accessible endpoint.

Breaking this down we can see a security principal identifier, a resource identifier indicating the device registration service, and a service endpoint which indicates the Azure Active Directory Password Protection service. What this tells us is Microsoft is piggybacking off the existing Azure Active Directory Device Registration Service for onboarding of the proxy agents.

Next up an authenticated HTTP POST is made to https://enterpriseregistration.windows.net/aadpasswordpolicy/<tenantID>/proxy?api-version=1.0. The bearer token for the global admin is used to authenticate to the endpoint. Here we have the Proxy Service posting a certificate signing request (CSR) and providing its fully qualified domain name (FQDN). The request for a CSR tells us the machine must have provisioned a new private/public key pair and once this transaction is complete we should have a signed certificate identifying the proxy.

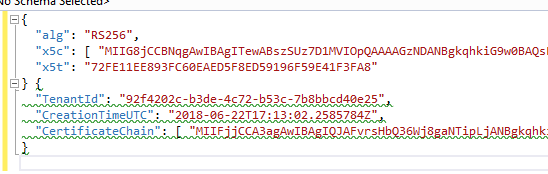

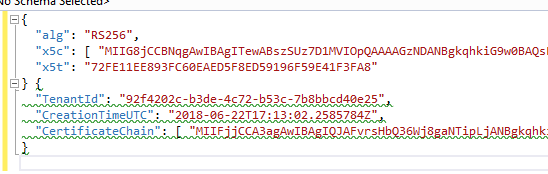

The endpoint responds with a JSON response.

If we open up and base64 decode the value in the SignedProxyCertificateChain we see another signed JSON response. Decoding the response and dropping it into Visual Studio shows us three attributes of note, TenantID, CreationTime, and the CertificateChain.

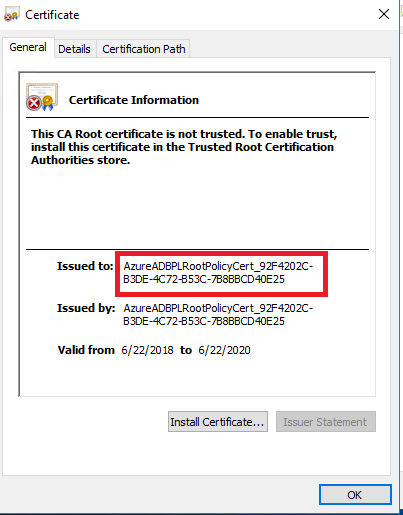

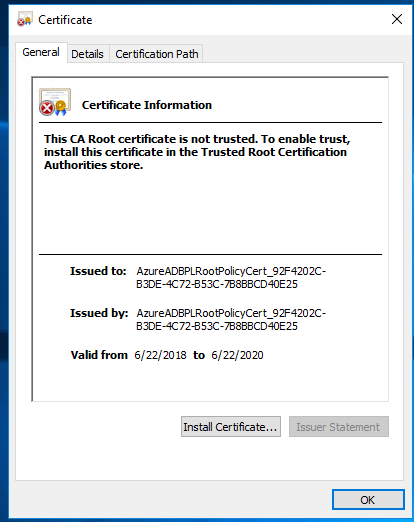

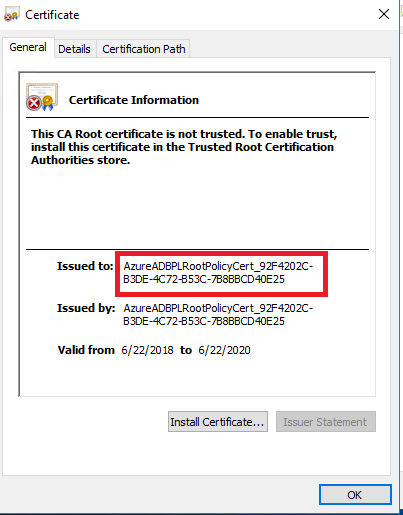

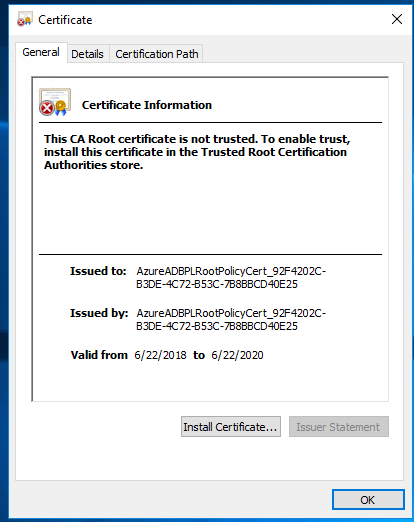

Dropping the value of the CertificateChain attribute into Notepad and saving it as a certificate yields the result below. Note the alphanumeric string after the AzureADBPLRootPolicyCert in the issued to section below.

My first inclination after receiving the certificate was to look into the machine certificate stores. I did that and they were empty. After a few minutes of confusion I remembered the documentation stating the registration of the proxy is a onetime activity and that it was mentioned it requires domain admin in the forest root domain and a quick blurb about a service connection point (SCP) and that it needed to be done once for a forest. That was indication enough for me to pop open ADSIEDIT and check out the Configuration directory partition. Sure enough we see that a new container has been added to the CN=Services container named Azure AD Password Protection.

Within the container there is a container named Forest Certs and a service connection point named Proxy Presence. At this point the Forest Certs container is empty and the object itself doesn’t have any interesting attributes set. The Proxy Presence service connection point equally doesn’t have any interesting attributes set beyond the keywords attribute which is set to an alphanumeric string of 636652933655882150_5EFEAA87-0B7C-44E9-B25C-4F665F2E0807. Notice the bolded part of the string has the same pattern as the what was in the certificate included in the CertificateChain attribute. I tried deleting the Azure AD Password Protection container and re-registering to see if these two strings would match, but they didn’t. So I’m not sure what the purpose of that string is yet, just that it probably has some relationship to the certificate referenced above.

The next step in the Proxy Service configuration process is to run the Register-AzureADPasswordProtectionForest cmdlet. This cmdlet again requires the Azure identity being used is a member of the global admins role and that the security principal running the cmdlet has membership in the domain administrators group. The cmdlet takes a few seconds to run and completes successfully.

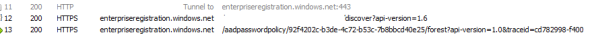

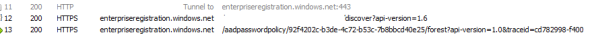

Opening up Fiddler shows additional conversation with Azure AD.

Session 12 is the same unauthenticated HTTP GET to the discovery endpoint that we saw above. Session 13 is another authenticated HTTP POST using the global admin’s bearer token to same endpoint we saw after running the last cmdlet. What differs is the information posted to the endpoint. Here we see another CSR being posted as well as providing the DNS name, however the attributes are now named ForestCertificateCSR and ForestFQDN.

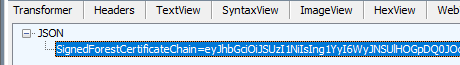

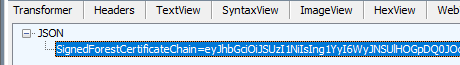

The endpoint again returns a certificate chain but instead using the attribute SignedForestCertificateChain.

The contents of the attribute look very similar to what we saw during the last cmdlet.

Grabbing the certificate out of the CertificateChain attribute, pasting it into Notepad, and saving as a certificate yields a similar certificate.

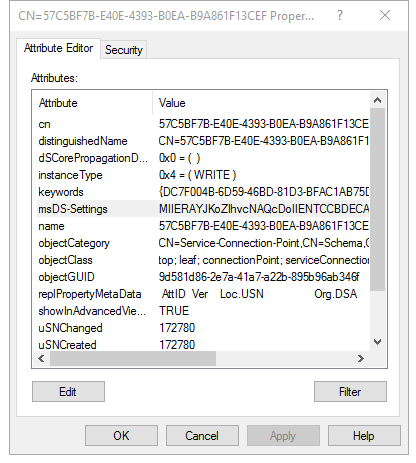

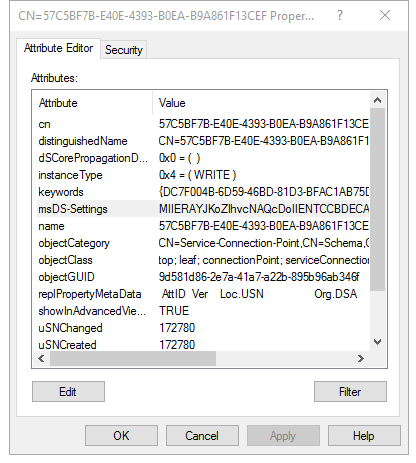

Bouncing back to ADSIEDIT and refreshing the view I saw that the Proxy Presence SCP didn’t change. We do see a new SCP was created under the Forest Certs container. Opening up the SCP we have a keywords attribute of {DC7F004B-6D59-46BD-81D3-BFAC1AB75DDB}. I’m not sure what the purpose of that is yet. The other attribute we now have set is the msDS-Settings attribute.

Editing the msDS-Settings attribute within the GUI shows that it has no values which obviously isn’t true. A quick Google search on the attribute shows it’s up to the object to store what it wants in there.

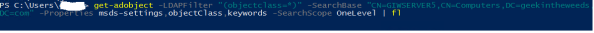

Because I’m nosey I wanted to see the entirety of the attribute so in comes PowerShell. Using a simple Get-ADObject query I dumped the contents of the attribute to a text file.

The result is a 21,000+ character string. We’ll come back to that later.

At this point I was convinced there was something I was missing. I started up WireShark, put a filter on to capture LDAP and LDAPS traffic and I restarted the proxy service. LDAP traffic was there alright over port 389 but it was encrypted via Kerberos (Microsoft’s typical habit). This meant a packet capture wouldn’t give me what I wanted so I needed to be a bit more creative. To get around the encryption I needed to capture the LDAP queries on the domain controller as they were processed. To do that I used a script. The script is quite simple in that it enables LDAP debug logging for a specific period of time with settings that capture every query made to the device. It then parses the event log entries created in the Directory Services Event Log and creates a pipe-delimited file.

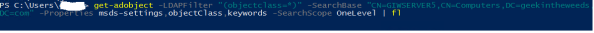

The query highlighted in red is what caught my eye. Here we can see the service for performing an LDAP query against Active Directory for any objects one level under the GIWSERVER5 computer object and requesting the properties of objectClass, msds-settings, and keywords attributes. Let’s replicate that query in PowerShell and see what the results look like.

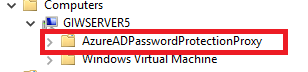

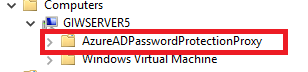

The results, which are too lengthy to paste here are there the computer object has two service connection point objects. Here is a screenshot from the Active Directory Users and Computers MMC that makes it a bit easier to see.

In the keywords attribute we have a value of {EBEFB703-6113-413D-9167-9F8DD4D24468};Domain=geekintheweeds.com. Again, I’m not sure what the purpose of the keyword attribute value is. The msDS-Settings value is again far too large to paste. However, when I dump the value into the TextWizard in Fiddler and base64 decode it, and dump it into Visual Studio I have a pretty signed JSON web token.

If we grab the value in the x509 Certificate (x5c) header and save it to a certificate, we see it’s the signed using the same certificate we received when we registered the proxy using the PowerShell cmdlets mentioned earlier.

Based upon what I’ve found in the directory, at this point I’m fairly confident the private key for the public private key pair isn’t saved within the directory. So my next step was to poke around the proxy agent installation directory of

C:\Program Files\Azure AD Password Protection Proxy\. I went directly to the logs directory and saw the following logs.

Opening up the most recent RegisterProxy log shows a line towards the bottom which was of interest. We can see that the encrypted proxy cert is saved to a folder on the computer running the proxy agent.

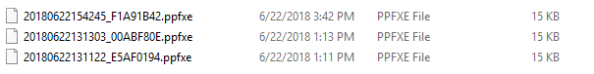

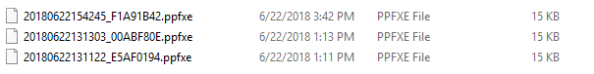

Opening the \Data directory shows the following three ppfxe files. I’ve never come across a ppfxe file extension before so I didn’t have a way of even attempting to open it. A Google search on the file extension comes up with nothing. I can only some it is some type of modified PFX file.

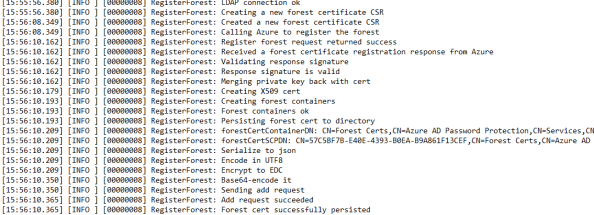

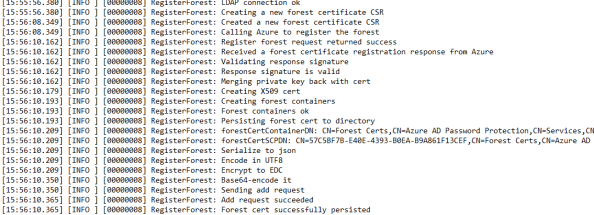

Did you notice the RegisterForest log file in the screenshot above? I was curious on that one so I popped it open. Here were the lines that caught my eye.

Here we can see the certificate requested during the Register-AzureADPasswordProtectForest cmdlet had the private key merged back into the certificate, then it was serialized to JSON, encoded in UTF8, encrypted, base64 encoded, and written to the directory to the msDS-Settings attribute. That jives with what we observed earlier in that dumping that attribute and base-64 decoding it gave us nothing decipherable.

Let’s summarize what we’ve done and what we’ve learned at this point.

- The Azure Active Directory Password Protection Proxy Service has been installed in GIWSERVER5.

- The cmdlet Register-AzureADPasswordProtectionProxy was run successfully.

- When the Register-AzureADPasswordProtectionProxy was run the following actions took place:

-

- GIWSERVER5 created a new public/private keypair

-

- Proxy service performs discovery against Azure AD to discover the Password Protection endpoints for the tenant

-

- Proxy service opened a connection to the Password Protection endpoints for the tenant leveraging the capabilities of the Azure AD Device Registration Service and submits a CSR which includes the public key it generated

-

- The endpoint generates a certificate using the public key the proxy service provided and returns this to the proxy service computer

-

- The proxy service combines the private key with the public key certificate and saves it to the C:\Program Files\Azure AD Password Protection Proxy\Data directory as a PPFXE file type

-

- The proxy service connects to Windows Active Directory domain controller over LDAP port 389 using Kerberos for encryption and creates the following containers and service connection points:

-

-

- CN=Azure AD Password Protection,CN=Configuration,DC=XXX,DC=XXX

-

-

- CN=Forest Certs,CN=Azure AD Password Protection,CN=Configuration,DC=XXX,DC=XXX

-

-

-

- CN=Proxy Presence,CN=Azure AD Password Protection,CN=Configuration,DC=XXX,DC=XXX

-

-

- CN=AzureADPasswordProtectionProxy,CN=GIWSERVER5,CN=Computers,DC=XXX,DC=XXX

-

-

-

- Writes signed JSON Web Token to msDS-Settings attribute for

-

-

-

- Writes keyword attribute (can’t figure out what this does yet)

- The cmdlet Register-AzureADPasswordProtectionForest was run successfully

- When the Register-AzureADPasswordProtectionForest was run the following actions took place:

-

- GIWSERVER5 created a new public/private keypair

-

- Proxy service performs discovery against Azure AD to discover the Password Protection endpoints for the tenant

-

- Proxy service opened a connection to the Password Protection endpoints for the tenant leveraging the capabilities of the Azure AD Device Registration Service and submits a CSR which includes the public key it generated

-

- The endpoint generates a certificate using the public key the proxy service provided and returns this to the proxy service computer

-

- The proxy service combines the private key with the public key certificate and saves it to the C:\Program Files\Azure AD Password Protection Proxy\Data directory as a PPFXE file type

-

- The proxy service connects to Windows Active Directory domain controller over LDAP port 389 using Kerberos for encryption and creates the following containers:

-

-

- CN=<UNIQUE IDENTIFIER>,CN=Forest Certs,CN=Azure AD Password Protection,CN=Configuration,DC=XXX,DC=XXX

-

-

-

- Writes to msDS-Settings the encoded and encrypted certificate it received back from Azure AD including the private key

-

-

-

- Writes to keyword attribute (not sure on this one either)

Based upon observation and review of the logs the proxy service creates when registering, I’m fairly certain the private key and certificate provisioned during the Register-AzureADPasswordProtectionProxy cmdlet is used by the proxy to make queries to Azure AD for updates on the banned passwords list. Instead of storing the private key and certificate in the machine’s certificate store like most applications do, it stores them in a PPFXE file format. I’m going to assume there is some symmetric key stored someone on the machine that is used to unlock the use of that information, but I couldn’t determine it with Rohitab API Monitor or Sysinternal Procmon.

I’m going to theorize the private key and certificate provisioned during the Register-AzureADPasswordProtectionForest cmdlet is going to be used by the DC agents to communicate with the proxy service. This would make sense because the private key and certificate are stored in the directory and it would make for easy access by the domain controllers. In my next post I’ll do a deep dive into the DC agent so I’ll have a chance to get more evidence to determine if the theory holds.

On a side note, I attempted to capture the web traffic between the proxy service and Azure AD once the service was installed and registered. Unfortunately the proxy service doesn’t honor the system proxy even when it’s configured in the global machine.config. I confirmed that the public preview of the proxy service doesn’t support the usage of a web proxy. Hopefully we’ll see that when it goes general availability.

Have a great week.