The Problem

Welcome back fellow geeks! I hope you all are staying healthy and not going too stir crazy being stuck at home. I’m here tonight to help break the monotony and walk you through a fun lab I recently put together.

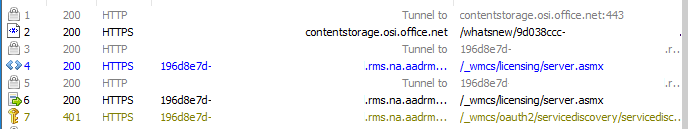

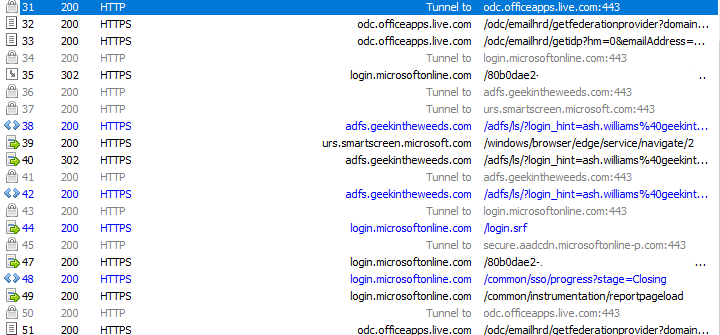

I recently had a customer building out a sandbox environment for experimentation in Microsoft Azure. For this environment the customer opted to setup a S2S VPN (site-to-site virtual private network) to establish connectivity between their on-premises data center and Azure. The customer had requirements to use BGP (border gateway protocol) to exchange routes between on-premises and Azure. Additionally, their security team required all Internet-bound traffic be piped back on-premises (force tunneling) through a set of security appliances before being egressed out to the Internet from their data center.

While I’ve setup connectivity with Azure in the past using an S2S VPN, it was with a policy-based VPN vs a route-based VPN that utilized BGP. I’ve also worked with a lot of customers that had requirements for forced tunneling, but never got involved much in the implementation. My customers typically use Microsoft ExpressRoute for connectivity with on-premises and a third-party NVA (network virtual appliance) like a Palo Alto or Imperva. Since I’m not cool enough to have a lab with ExpressRoute and I’m too cheap to pay for an NVA, I’ve never had a chance to do the implementation myself. This has meant relying on documentation and other folks within Microsoft that have had that experience.

Beyond the implementation gap in that pattern, I also have gaps in my BGP skill set. While I’ve been lucky enough to play with a lot different technologies over the course of my career, enterprise routing was one area I never got to dive deep in. Over my time at Microsoft and AWS, I’ve had to learn the concepts of the protocol and how to use it within the public cloud, but still have lacked any practical implementation experience.

If you know me, you know I hate not being able to implement the technologies I speak with customers about. Hence, this blog post was born. I’ll be walking you through the lab I built to address the gaps in my BGP and get some practical experience force tunneling traffic. Enough with my blabbing, let’s get into it.

Lab Environment

The complete lab setup I used is illustrated above. In my home lab I’m using the 192.168.100.0/24 address range and have assigned the .1 address to the pfSense interface. Another interface on the device has been configured for DHCP to receive a public IP address from my ISP. Within Azure I’ve setup a single VNet (Virtual Network) assigned the address block of 10.0.0.0/16. Within the VNet I’ve create five subnets each using a /24 block of address space (I’m terrible at subnetting).

Inside the GatewaySubnet I’ve provisioned a VPN VNG (Virtual Network Gateway) with the VpnGw2 SKU to support BGP. The subnet named primary contains a single Windows Server 2016 VM (Virtual Machine) that I’ll be using to test the setup. Azure Bastion sits in the Azure Bastion subnet providing me with remote access into the VM.

Finally, an Azure Firewall instance has been provisioned using the new forced tunneling feature in preview. To support this feature, I’ve provisioned two subnets, one named AzureFirewallSubnet and one named AzureFirewallManagementSubnet as well as two public IPs. To route the traffic as needed, I’ve created three route tables with some user defined routes.

For this post I’m going to walk through the setup of the S2S VPN tunnel. Anytime I can refer you to official documentation for a step-by-step process, I’ll include a hyperlink. The steps that aren’t documented in a single place or documented at all will be the steps I’ll cover in detail.

The first thing you need to do is provision a VNet (Virtual Network). The VNet must at least include a subnet named GatewaySubnet. Microsoft requires this name for the subnet in order to deploy a VNG (Virtual Network Gateway). You’ll additionally want to provision another subnet named whatever you want to hold the VM (virtual machine) to test connectivity with. If you want to use Azure Bastion for remote access to the VM, you’ll need a third subnet which must be named AzureBastionSubnet.

While you’re twiddling your thumbs for 20 minutes waiting for the VNG, optional Bastion, and VM, you can create the local network gateway. The local network gateway is a logical resource in Azure which represents your on-premises VPN appliance. To set this resource up you’ll need a few different items:

- The public IP address in use by your VPN appliance

- The BGP peer address you’ll be peering with Azure

- The ASN (autonomous system number) you’re using on-premises

For this lab you’ll want to use a private ASN between 64512-65514 or 65521-65534.

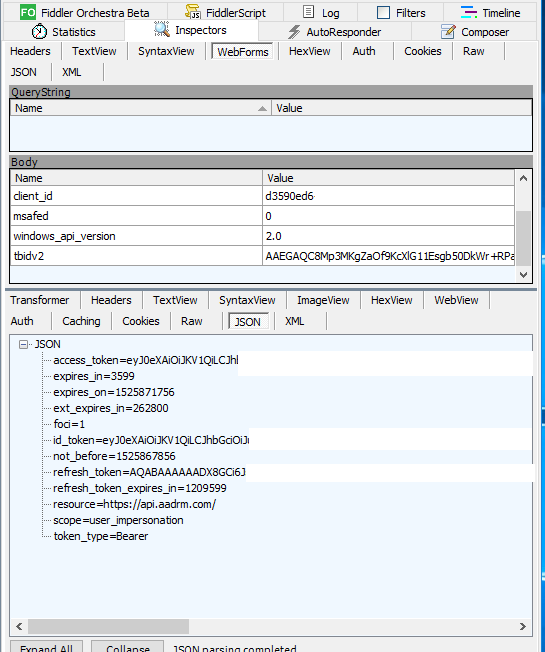

Below is a screenshot of my configuration. I included the entire address space I’m going to advertise, but if you’re using BGP you only need to include the addresses you’ll be using as BGP peer.

Now that Azure is provisioning all your necessary resources, it’s a good time to bounce over to pfSense. Note that pfSense doesn’t provide BGP support. For that you’ll need to add the OpenBGPD package. To do that you’ll navigate to the System drop down menu and choose Package Manger. Search for BGP and install the OpenBGP package. Once complete you’ll see it as an installed package as seen below.

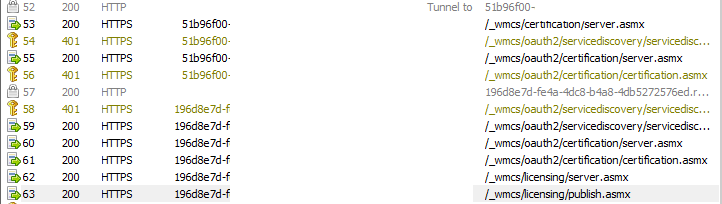

Once the VPN Gateway has been provisioned you can begin configuration of the connection. The connection is also represented in Azure as a logical resource. There isn’t much to configure when you create the connection through the Portal. If you configure it through PowerShell, CLI, or an ARM template, you’ll have the flexibility to tweak the configuration of the tunnel. This includes the ability to limit the encryption ciphers and hashing algorithms supported on the Azure end. Once the connection is provisioned, open up the resource blade for it, go to the Configuration menu item in the Settings section and toggle BGP to Enabled.

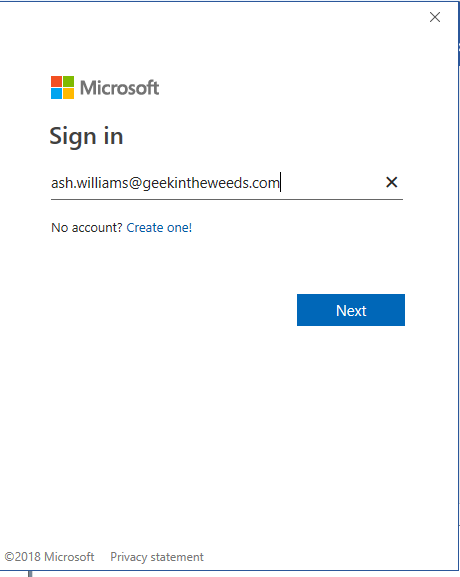

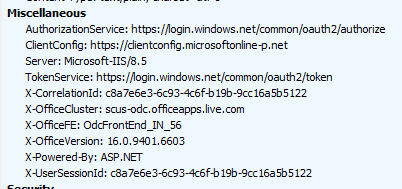

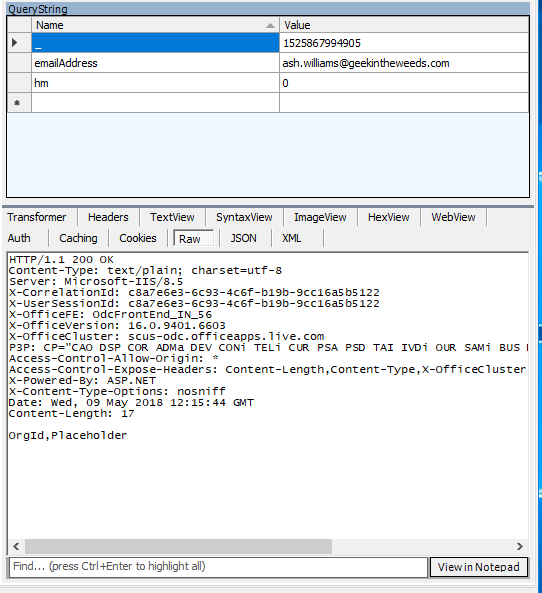

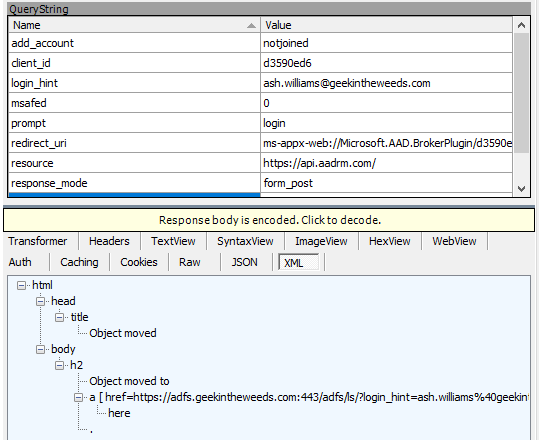

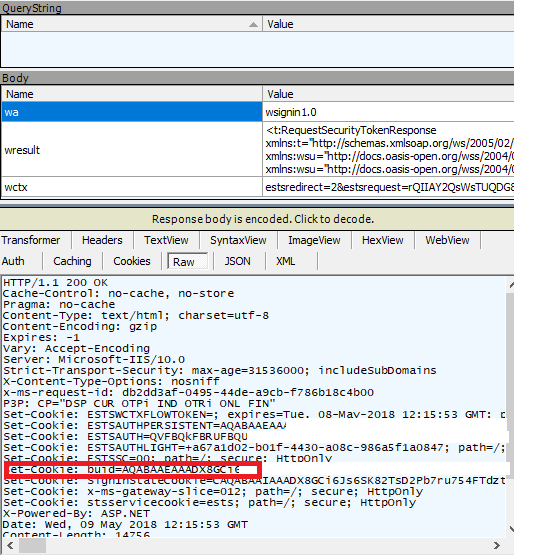

Before you bounce over to pfSense and configure that end, you’ll need a few pieces of information from the VPN Gateway. Within the Portal open up the VNG resource blade. Note the public IP address that has been assigned to the VNG. You’ll need this for the pfSense setup.Next click the Configuration menu item in the Settings section. Here you’ll want to check off the Configure BGP ASN check box and note the ASN (by default 65515) and the BGP peer IP address because you’ll need them later. Click Save once you complete. This change will take around 5 minutes.

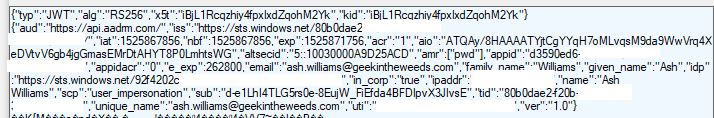

It’s now time to hop over to pfSense. From the main menu navigate to the VPN drop down menu and choose the IPsec option. You’ll first need to create a IKE Phase 1 entry to establish the authentication for the tunnel.In the General Information section ensure the Key Exchange Version box is populated with IKEv2 and the Remote Gateway is populated with the public IP address of the VNG. In the Phase 1 Proposal (Authentication) section, choose to the Mutual PSK (Pre-Shared Key) option, the My identifier is set to My IP Address and Peer identifier set to Peer IP address. Plus in the PSK you setup in Azure.In the Phase 1 Proposal (Encryption Algorithm) section pick your preferred encryption algorithm, key length, hashing algorithm, and Diffie-Hellman Group.The Azure end supports a number of cryptographic combinations just be aware you’ll need to configure a custom IPSec Policy using the CLI, PowerShell, or ARM template if you pick a combination that isn’t offered by default. I’m not sure what it supports by default because I couldn’t find any documentation on it. It seems like you’ll be forced to use DHGroup2 if you create through the Azure Portal, which you really shouldn’t be using due the small key length. If you want to nerd out a bit, take a read through this document. I wanted to bump this up to DHGroup24, so I opted to create the custom IPSec policy with the configuration below.

ipsecpol = New-AzIpsecPolicy -IkeEncryption AES256 -IkeIntegrity SHA256 -DhGroup Dhgroup24 -IpsecEncryption GCMAES256 -IpsecIntegrity GMAES256 -PfsGroup None -SALifeTimeSeconds 28800

Next up you need to configure a Phase 2 entry which will control how traffic is carried across the tunnel. Expand the Phase 1 entry you created and click the Add P2 button to add a phase 2 entry. In the General Information section you’ll want to set the Local Network option to Network with an address of 0.0.0.0/0. This will allow us to tunnel traffic to any address through the VPN tunnel which will support our use case for the forced tunneling we’ll create later on. In the Remote Network section, set it to the CIDR block of the VNet.In the Phase 2 proposal configure the settings to support whatever encryption setup you’re using. For my configuration, I set it up as seen in the screenshot below.

Once the phase 2 entry is configured, navigate to the Status drop-down menu and choose IPsec. Click the Connect button and assuming you configured everything correctly, the status shift from Disconnected, to Connecting, and will end on Established as seen below.

Hurray, you have an established VPN tunnel. Now it’s time to configure BGP.

Since you’ve already toggled the appropriate options in Azure to support BGP, it’s now time to configure it in pfSense. You will first need to create a firewall rule to allow the BGP traffic to flow between Azure and the pfSense box. To do this you’ll select the Firewall drop-down menu and choose the Rules option. Create a new rule to allow TCP port 179 from the source of the Azure BGP peer IP you noted earlier to the pfSense interface IP for the network you’re connecting to Azure.

Next you have to open the Services drop-down menu and choose OpenBGPD.In this section you have a few menu options, one which allows you to modify the raw config. Like the idiot I am, I ignored the comment at the beginning of the raw config that says not to edit it. After editing it, I was unable to configure using the menu options. If you’re not an idiot like me, you should be able to configure it using the menus. My working config is illustrated below.

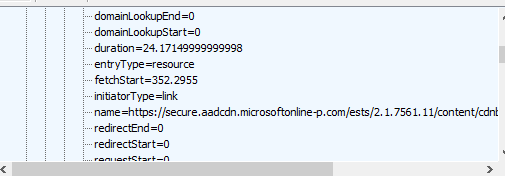

Once you have your Config set, save it and give it a minute. The navigate to the Status section of the OpenBGPD service. Scroll to the bottom and check out the OpenBGPD Neighbors section. If you’ve misconfigured anything you’ll receive an error that the log file can’t be written (useful right?)

Once you have your Config set, save it and give it a minute. The navigate to the Status section of the OpenBGPD service. Scroll to the bottom and check out the OpenBGPD Neighbors section. If you’ve misconfigured anything you’ll receive an error that the log file can’t be written (useful right?)

Additionally when I check the effective routes for the network interface of the VM in Azure I can see the routes propagating into the VM’s subnet.

You can validate your connectivity at this point in any number of ways. I went the lazy route and used pfSense’s Test Port capability located in the Diagnostics drop-down menu. Make sure that you open the appropriate rules in any NSGs between you and the VM. Also consider the VM’s host firewall if you opt to use a non-standard port or protocol like ICMP. If you opt to test from Azure back on-premises, make sure to open the appropriate firewall rules in the pfSense firewall for the IPSec interface.

With that you have a working S2S VPN complete with BGP exchange of routes. That will wrap up this post. In the next post I’ll walk through the configuration of forced tunneling with Azure Firewall.

Continue the journey in the second post.