2/11/2025 Update – This action is now captured in the Entra ID Audit Logs! I’d recommend putting an alert in ASAP to track this moving forward.

Hello fellow geek!

Today I’m going to cover a topic that isn’t well understood in the Azure community and can present significant risk to your Azure estate. Sit back, grab your Friday morning coffee, and prepare to learn about the “real” root management group.

Microsoft made an interesting identity-based choice when architecting Azure. That choice was to have all Azure subscriptions share a common identity management plane in what we have known as Azure AD (Azure Active Directory) and which has recently been renamed Entra ID. The shared identity management plane in Azure creates a single authority for identity data and authentication while maintaining separate authorization boundaries between Azure subscriptions. This concept may differ for those of you coming from AWS (Amazon Web Services) where every AWS account has a unique identity management plane that has its own identity data store, authentication boundary, and authorization boundary. Microsoft’s decision comes with benefits and considerations.

The atomic unit for resources in Microsoft Azure is the Azure subscription which acts as an authorization boundary, limits boundary, and compliance boundary. Each Azure subscription can be associated to a single Entra ID tenant. Once a subscription is associated to an Entra ID tenant the subscription will use tenant as a source of identity data and authentication provider. This dependency on Entra ID creates an interesting security risk around authorization.

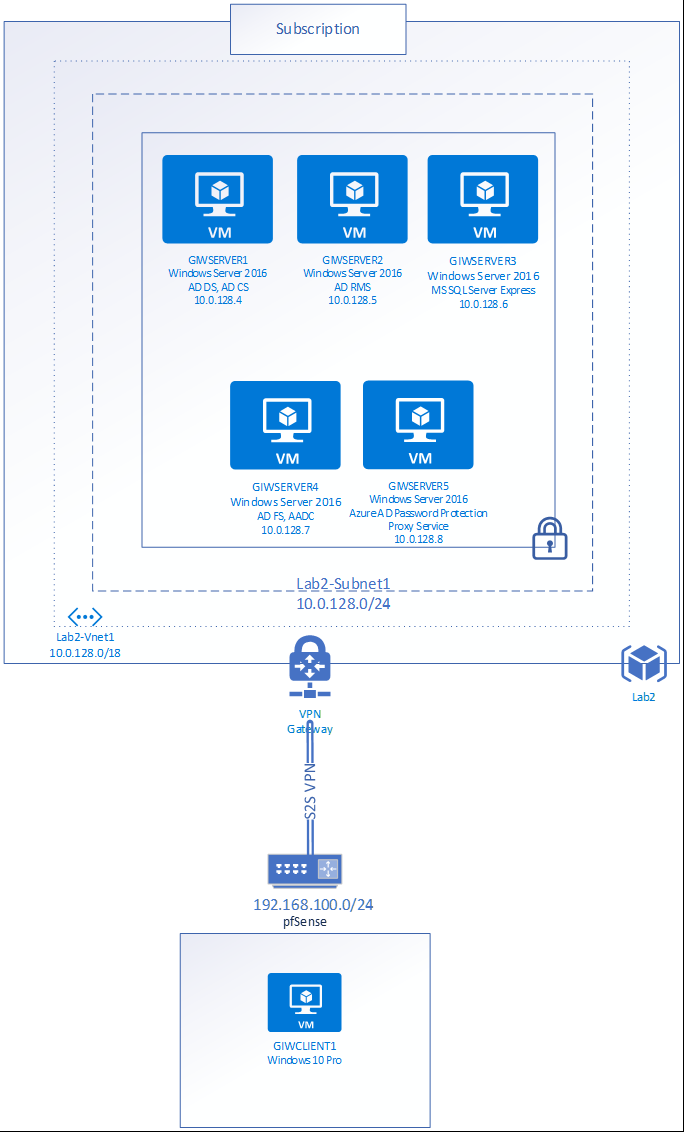

Before I dive into the details of this, let me briefly explain the concept of management groups. A management group in Azure is a logical container for Azure Subscriptions which allow for you to enforce configuration “how a resource looks” (Azure Policy) and authorization “what a user can do” (Azure RBAC) across one or more subscriptions. Prior to management groups, these things had to be managed at the individual subscription level or below (resource group or individual resource). Every subscription added to an Entra ID tenant exists under the Tenant Root Management Group by default, but this can be changed. Customers can can create additional management groups underneath the Tenant Root Management Group as per their needs (great guidance on this here).

If you’ve used Azure for any length of time the above is likely all review for you. However, as Yoda said, “there is another”. Above the Tenant Root Management Group exists another management group called root or “/”. As seen in the visual below, the root management group is the glue that sticks Entra ID authorization to Azure authorization together. Let’s dig into how this works.

In Entra ID there is a role called Global Administrator. For those of you unfamiliar with this role, it is the god role of Entra ID and all services associated with an Entra ID tenant such as M365 and, yes, Azure. Holding this role in Entra ID does not give you permissions in Azure, but there is a path to give yourself permissions and become the god of your Azure estate.

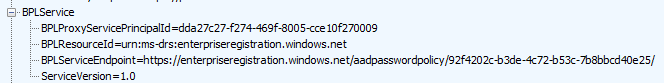

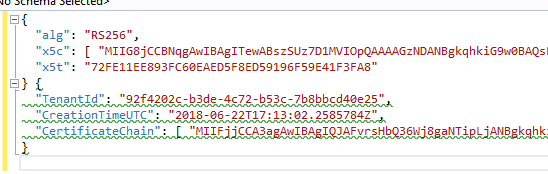

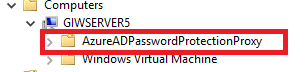

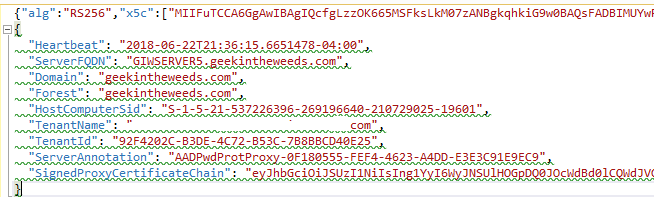

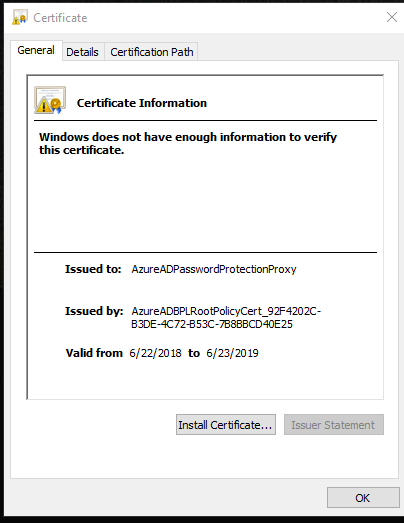

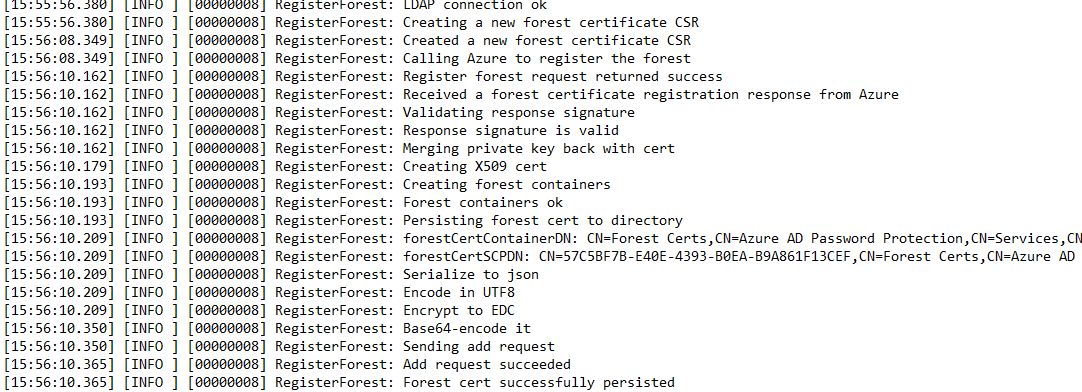

Users who hold the Global Administrator have the ability to grant themselves access on the root “/” management group. They can do this through an option in the Entra ID blade of the Azure Portal called Access Management for Azure Resources or Elevate Access. This is also available via the Azure REST API using the elevateAccess endpoint. The value of this toggle switch shown in the Portal is the value for the current user context (user logged into the Portal). You cannot view this toggle switch for other users, but we can tell if it’s been toggled on as I will show later.

When a Global Administrator toggles this option either through the Portal or through the REST API an Azure RBAC Role Assignment for the User Access Administrator is created at the root “/” management group.

The User Access Administrator is a highly privileged role granting the user full permissions over the Microsoft.Authorization resource provider (as seen below). These permissions allow the user to create additional role assignments on for any Azure RBAC Role on any Azure management, subscription, resource group, or resource within the Entra ID tenant. Yes… yikes.

{

"id": "/providers/Microsoft.Authorization/roleDefinitions/18d7d88d-d35e-4fb5-a5c3-7773c20a72d9",

"properties": {

"roleName": "User Access Administrator",

"description": "Lets you manage user access to Azure resources.",

"assignableScopes": [

"/"

],

"permissions": [

{

"actions": [

"*/read",

"Microsoft.Authorization/*",

"Microsoft.Support/*"

],

"notActions": [],

"dataActions": [],

"notDataActions": []

}

]

}

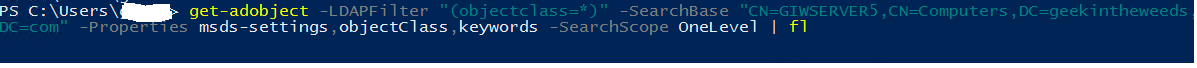

}As I mentioned earlier, the Portal will only show you the value of the toggle switch for the ElevateAccess feature for the currently logged in user. You may now be thinking “How the heck can I enforce this if I can’t view it in the Portal?”. The good news is this toggle seems to be some backend orchestration where the platform checks whether the user has the User Access Administrator RBAC Role Assignment on the root “/” management group. This means you don’t need to care about that visual toggle switch, you only need to care about the actual permission. You can list out the the users that have the role assignment at root using the cli command below.

az role assignment list --scope "/" --query "[?roleDefinitionName=='User Access Administrator'].{Username:principalName, ObjectId:objectId}" --output tableAwesome, so you know who has it. Why should you care? Listen, I gonna be nice and assume you’re asking this because it’s a Friday and your brain is fried. The reason you should care is this gives your users who have access to the Entra ID Global Administrators Role the ability to make themselves god of your Azure estate. This includes owners over the resources for management plane operations which can, in almost every instance, lead to owner of the data contained within the resources within the data plane. You SHOULD NOT have a role assignment for User Access Administrator on the root “/” management group. There a few instances where you need this permission temporarily to grant other permissions, but I will cover that at the end of this post. For now, know that if you have that permission there you shouldn’t.

In most enterprises there is a separate team managing Entra ID from the team managing Azure in order to maintain separation of duties. Access to the Global Administrator role opens up the risk for the user to assert access and control over data that is outside of their roles and responsibilities. While there is no way to stop this from happening, you should be monitoring for when it occurs. So how might you do this?

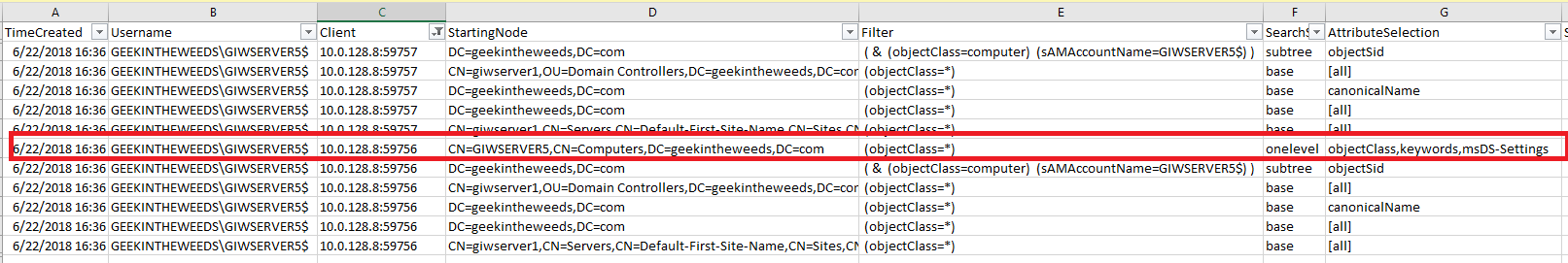

If you’re used Azure, you should be familiar with Azure Activity Logs. The Activity Logs contain log entries for create, update, and delete operations on the Azure management plane. Activity Logs exist at a number of scopes including Subscription, Management Group, and Directory. While Subscription and Management Group Activity Logs supports integration with Azure Monitor Diagnostic Logs, Directory Activity Logs do not and those are the logs new role assignments to the root “/” management group are recorded in. This means you need to write custom code to manually pull down those logs via the REST API in order to capture and alert on them in your favorite SIEM. Yuck right? Well there is an easier way to alert on this.

A while back Microsoft introduced support for Azure Monitor to make log queries against the Azure Resource Graph. I’m not going to do a deep dive into ARG (Azure Resource Graph). All you need to know for the purpose of this post is it’s a service you can tap into to pull down information about Azure resources, including role assignments.

Let me walk through how this works.

I can issue an Kusto query through Azure Monitor to query ARG to see what role assignments for User Access Administrator exist on the root “/” management group using the query below (note this will require you have appropriate read permissions at root “/”).

arg("").AuthorizationResources

| where properties.scope == "/"

| where properties.roleDefinitionId == "/providers/Microsoft.Authorization/RoleDefinitions/18d7d88d-d35e-4fb5-a5c3-7773c20a72d9"This Kusto query will query the ARG authorizationresources category for any role assignments on the root “/” management group that have the role definition id for User Access Administrator. Each resulting log entry denotes a role assignment on root. Here we can see I have two role assignments on the root for User Access Administrator. Bad Matt.

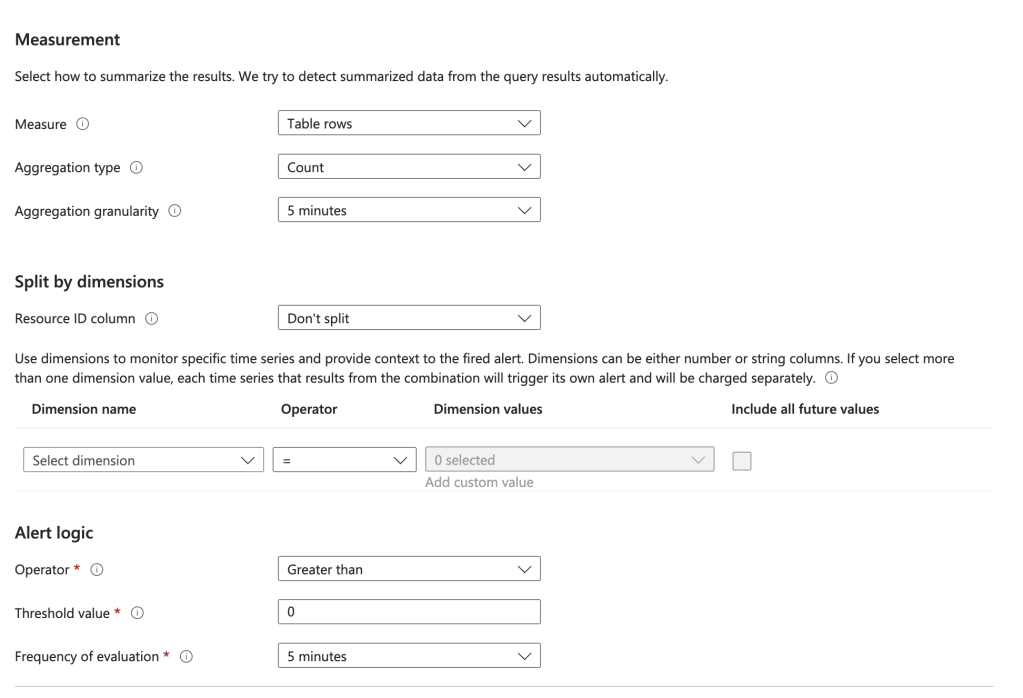

Back in October 2023 Microsoft introduced into public preview support to create Azure Alerts for Azure Monitor Log queries against ARG. This means you can create an Azure Alert based on this custom log query. If there is a role assignment for User Access Administrator on the root “/” management group, an alert will be fired. Let me walk through the setup of that alert, because it’s a little bit funky.

First thing you will need to do is create an action group and you can use this documentation to that. Once you have your action group you’ll want to navigate to the Alerts blade in the Azure Portal and then to the alert rules

Select the option to create a new Alert Rule. In the scope section you can select a subscription. If you are using a similar subscription design as to the Azure Cloud Adoption Framework, selecting the Management subscription would be a good choice. I don’t believe the choice matters much because the alert is on the root management group and not a resource within a subscription.

On the condition screen you will choose the Custom log search option for the Signal name. The query you’ll put in there is below.

arg("").AuthorizationResources

| where properties.scope == "/"

| where properties.roleDefinitionId == "/providers/Microsoft.Authorization/RoleDefinitions/18d7d88d-d35e-4fb5-a5c3-7773c20a72d9"You will will also need to configure the measurements. You can use the settings I have below or customize it to your liking.

On the Actions screen choose Select action groups and select the action group you configured before.

On the Details screen you can set the severity to whatever you want. I’d recommend 0 since this is a significant escalation of privilege. You will also need to configure the alert with a managed identity. It will need an identity to authenticate and be authorized to ARG. Choose whichever managed identity type makes sense for your organization.

Add whatever tags you want on the next screen and create the alert.

Done right? No, we now need to give the managed identity permissions on the root management group to read the role assignments.

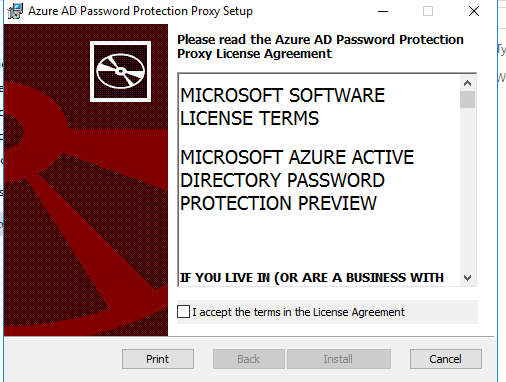

I promised earlier I’d tell you the instance where you need to use this elevation. The are very few instances where you need to do this. One instance is when you are first building out your management group structure. In that scenario, no one has permission over the root or tenant root management group so no one can create new management groups. You will need to elevate a user with Global Administrator to the User Access Administrator role on the root “/” in that situation so that use can then grant another user account owned by the Azure team (ideally non-human, but vaulted is good too) User Access Administrator on the Tenant Root Management Group. When complete, the Global Administrator should toggle that switch back to off to remove the RBAC role assignment. This Microsoft article explains a few other scenarios you may need to temporary grant this role to grant permissions at the root “/”.

Now back to setting up the alert rule. Next up you need to grant the managed identity you assigned to the alert rule the permission at the root “/” management group so it can query the role assignments (see, a use case!). You can find the object id of the managed identity in the identity section of the Alert in the Portal. What role you assign it is up to you. I’m doing Reader because I’m lazy, but you could certainly craft a custom role if you’d like to (don’t forget to remove your permissions once you’ve completed this!).

az role assignment create --assignee-object-id "4f984694-b43c-4528-87e9-68aeab7478a3" --scope "/" --role "Reader"You’re good to go! You now have an alert that will fire anytime there is any role assignment for User Access Administrator on the root “/” management group. Again, there should never be a role assignment for that role unless you’re temporarily using it for one of the use cases above.

The key things I want you to take away from this this post is the critical role Entra ID plays across all of the Microsoft Clouds. It’s important to understand how privilege in one product (Entra ID) can lead to privilege in another (Azure). Now you have a quick and easy security win you can crank out before Thanksgiving. Enjoy!