Updates:

7/2025 – Updated post with DNS Security Policy support for DNS query logging. Tagged scenario 4 as deprecated. Corrected image and description of flow in 3b

This is part of my series on DNS in Microsoft Azure.

- DNS in Microsoft Azure – Azure-provided DNS

- DNS in Microsoft Azure – Azure Private DNS

- DNS in Microsoft Azure – Azure Private DNS Resolver

- DNS in Microsoft Azure – PrivateLink Private Endpoints

- DNS in Microsoft Azure – PrivateLink Private Endpoints and Private DNS

- DNS in Microsoft Azure – Private DNS Fallback

- DNS in Microsoft Azure – DNS Security Policies

Today I’ll be continuing my series on DNS in Microsoft Azure. In my first post I covered fundamental concepts of DNS resolution in Azure such as the 168.63.129.16 virtual IP and Azure-provided DNS. In the second post I went over the Azure Private DNS service and it’s benefits over the default virtual network namespaces. In this post I’m going to cover the Azure Private DNS Resolver.

A majority of organizations have an existing on-premises IT footprint. During the move into Azure, these organizations need to support communication between users and applications on-premises or in other clouds with services deployed into Azure. An important piece of this communication includes name resolution of DNS namespaces hosted on-premises and DNS namespaces hosted in Azure Private DNS Zones. This is where the Azure Private DNS Resolver comes in.

The Azure Private DNS Resolver was introduced into general availability in October 2022. It was developed to address two gaps of the Azure-provided DNS service. As I’ve covered in my prior posts the Azure-provided DNS services does not support resolution of DNS namespaces hosted in on-premises or other cloud DNS services when the DNS query is sourced from Azure. Neither does it support resolution of DNS namespaces hosted in Azure Private DNS Zones from machines on-premises or in another cloud without the customer implementing a 3rd-party DNS proxy. The Azure Private DNS Resolver fills both gaps without the customer having to implement a 3rd-party DNS proxy.

The Resolver (Azure Private DNS Resolver) consists of three different components which include inbound endpoints, outbound endpoints, and forwarding rule sets. Inbound endpoints provide a routable IP address that services running on-premises, in another cloud, or even in Azure can communicate with to resolve DNS namespaces hosted in Azure Private DNS Zones. Outbound endpoints provide a network egress point for DNS traffic to external DNS services running on-premises or within Azure. Forwarding rulesets are groups of DNS forwarding rules (conditional forwarders) that give direction to DNS traffic leaving a virtual network through the 168.63.129.16 virtual IP.

Let’s take a look at a few different scenarios and how this all works together.

Scenario 1 – On-premises machine needs to resolve an Azure Virtual Machine IP address where the DNS namespace is hosted in an Azure Private DNS Zone.

In this scenario an Azure Private DNS Resolver instance has been deployed a shared services virtual network. An Azure Private DNS Zone named mydomain.com has been linked to the virtual network. Connectivity to on-premises has been implemented using either an ExpressRoute or VPN connection. The on-premises DNS service has been configured with a conditional forwarder for mydomain.com with queries being sent to the inbound endpoint IP address at 10.1.0.4.

Let’s look at the steps that are taken for an on-premises machine to resolve the IP address of vm1.mydomain.com.

- The on-premises machine creates a DNS query for vm1.mydomain.com after validating it does not have a cached entry. The machine has been configured to use the on-premises DNS server at 192.168.0.10 as its DNS server. The DNS query is passed to the on-premises DNS server.

- The on-premises DNS server receives the query, validates it does not have a cached entry and that it is not authoritative for the mydomain.com namespace. It determines it has a conditional forwarder for mydomain.com pointing to 10.1.0.4 which is the IP address of the inbound endpoint for the Azure Private DNS Resolver running in Azure. The query is recursively passed on to the inbound endpoint over the ExpressRoute or Site-to-Site VPN connection.

- The inbound endpoint receives the query and recursively passes it into the virtual network through the outbound endpoint which passes it on to the Azure-provided DNS service through the 168.63.129.16 virtual IP.

- The Azure-provided DNS service determines it has an Azure Private DNS Zone linked to the shared services virtual network for mydomain.com and resolves the hostname to its IP address of 10.0.0.4.

Scenario 2 – Azure virtual machine needs to resolve an on-premises service IP address where the DNS namespace is hosted on an on-premises DNS server

There are two approaches to using the Resolver as a DNS resolution service for Azure services. There is a centralized architecture and distributed architecture. My peer Adam Stuart has done a wonderful analysis of the benefits and considerations of these two patterns. You will almost always use the centralized architecture. The exceptions will be for workloads that have a high number of DNS queries such as VDI. Both the inbound and outbound endpoints endpoints have a limit to the queries per second (QPS) so by using a decentralized architecture for resolution of on-premises namespaces you can mitigate the risk of hitting the QPS on the inbound endpoint. I suggest reading Adam’s post, it has some great details.

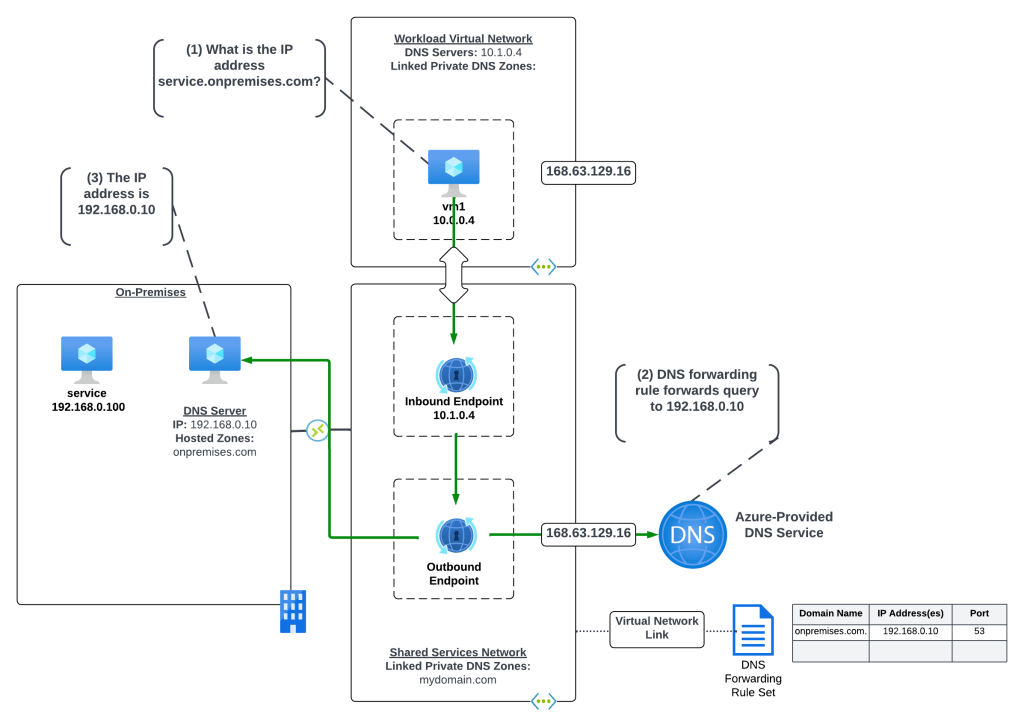

Scenario 2a – Centralized architecture for connected virtual networks

Let me first cover the centralized architecture because it’s the more common architecture and will work for most use cases.

In the centralized architecture all virtual networks in the environment have network connectivity to a shared services virtual network through direct or indirect (such as Azure Virtual WAN or a traditional hub and spoke) virtual network peering. The Resolver and its endpoints are deployed to the shared services virtual network, a DNS Forwarding Rule Set is linked to the shared services virtual network, and it has connectivity back on-premises through an ExpressRoute or VPN connection. This architecture centralizes all DNS queries across your Azure environment pushing them through the inbound endpoint (beware of those QPS limits!).

In the example scenario above, a rule has been configured in the DNS Forwarding Rule Set to forward traffic destined for the onpremises.com domain to the on-premises DNS service at 192.168.1.10. The on-premises DNS service is authoritative for the onpremises.com domain.

Let’s look at the query path for this scenario where a VM1 in Azure is trying to resolve the IP address for an application running on-premises named service.onpremises.com where the namespace onpremises.com is hosted in an on-premises DNS server.

- VM1 creates a DNS query for services.onpremises.com. VM1 does not have a cached entry for it so the query is passed on to the DNS Server configured for the VMs virtual network interface (VNIC). The DNS Server has been configured by the Azure DHCP Service to the Resolver inbound endpoint with IP address 10.1.0.4 via the DNS Server settings of the virtual network. The query is passed on to the inbound endpoint.

- The inbound endpoint receives the query and recursively passes it into the virtual network through the outbound endpoint and on to the 168.63.129.16 virtual IP address and on to the Azure-provided DNS service. The Azure-provided DNS service checks to see if there is an Azure Private DNS Zone linked to the virtual network the resolver endpoints are in with the name of onpremises.com. Since there is not, the DNS Forwarding Rule Set linked to the virtual network is processed and the rule for onpremises.com is matched and triggered causing the recursive DNS query to be sent out of the outbound endpoint and over the ExpressRoute or VPN connection to the on-premises DNS server at 192.168.0.10.

- The on-premises DNS server resolves the hostname to the IP address an returns the result.

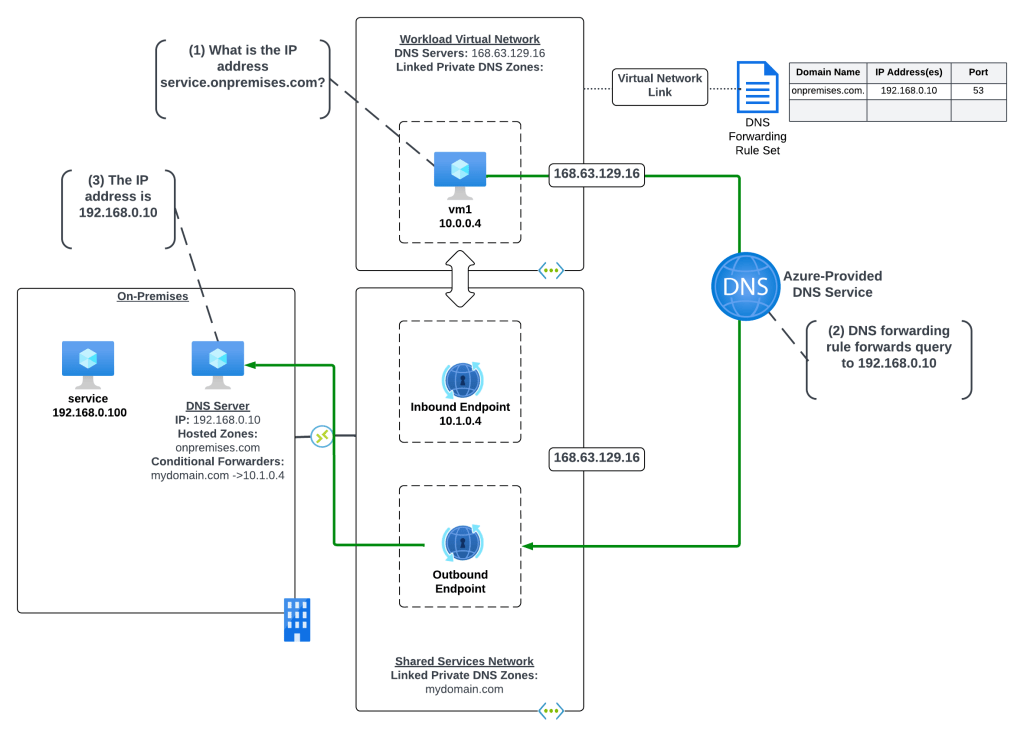

Scenario 2b – Distributed architecture for connected virtual networks

Let’s now cover the distributed architecture, which as Adam notes in his blog may be a pattern required if you’re hitting the QPS limits on the inbound endpoint.

In this distributed architecture all virtual networks in the environment have network connectivity to a shared services virtual network through direct or indirect (such as Azure Virtual WAN or a traditional hub and spoke) virtual network peering. The Resolver endpoints are deployed to the shared services virtual network which has connectivity back on-premises through an ExpressRoute or VPN connection. The workload virtual network DNS Server settings are set to the 168.63.129.16 virtual IP to use Azure-provided DNS. DNS Forwarding Rulesets are linked directly to the workload virtual networks and are configured with the necessary rules to direct DNS queries to the on-premises destinations.

In the above example, there is one rule in the DNS Forwarding Ruleset which is configured to forward DNS queries for onpremises.com to the DNS Server on-premises at 192.168.0.10.

Let’s look at the query path for this scenario where a VM1 in Azure is trying to resolve the IP address for an application running on-premises named service.onpremises.com where the namespace onpremises.com is hosted in an on-premises DNS server.

- VM1 creates a DNS query for services.onpremises.com. VM1 does not have a cached entry for vm3.mydomain.com so the query is passed on to the DNS Server configured for the VMs virtual network interface (VNIC). The DNS Server has been configured by the Azure DHCP Service to the 168.63.129.16 virtual IP which is the default configuration for virtual network DNS Server settings and which passes the query on to the Azure-provided DNS services.

- The recursive query is received by the Azure-provided DNS service and the rule for onpremises.com in the linked DNS Forwarding Ruleset is triggered passing the recursive query out of the outbound endpoint to the on-premises DNS server at 192.168.0.10. The recursive query is passed on over the ExpressRoute or Site-to-site VPN connection to the on-premises DNS server.

- The on-premises DNS server resolves the hostname to the IP address an returns the result.

Scenario 2c – Distributed architecture for isolated virtual networks

There is another pattern for the use of the distributed architecture which could be used for isolated virtual networks. Say for example you have a workload that needs to exist in an isolated virtual network due to a compliance requirement, but you still have a requirement to centrally manage DNS and log all queries.

In this variation of the distributed architecture the virtual network does not have any direct connectivity to the shared service virtual network through direct or indirect peering. The DNS Forwarding Ruleset is linked to the isolated virtual network and it contains a single rule for “.” which tells the Azure-provided DNS service to forward all DNS queries to the configured IP address.

Let’s look at the resolution of a virtual machine in the isolated virtual network trying to resolve the IP address of a publicly-facing API.

- VM1 creates a DNS query for my-public-api.com. VM1 does not have a cached entry for vm3.mydomain.com so the query is passed on to the DNS Server configured for the VMs virtual network interface (VNIC). The DNS Server has been configured by the Azure DHCP Service to the 168.63.129.16 virtual IP which is the default configuration for virtual network DNS Server settings and which passes the query on to the Azure-provided DNS service.

- The recursive query is received by the Azure-provided DNS service and the rule for “.” in the linked DNS Forwarding Ruleset is triggered passing the recursive query out of the outbound endpoint to the on-premises DNS server at 192.168.0.10. The recursive query is passed on over the ExpressRoute or Site-to-site VPN connection to the on-premises DNS server.

- The on-premises DNS server checks its own cache, validates it’s not authoritative for the zone, and then recursively passes the query to its standard forwarder.

- The public DNS service resolves the hostname to an IP address.

One thing to note about this architecture is there are some reserved Microsoft namespaces that are not included in the wildcard. This means that these zones will be resolved directly by the Azure-provided DNS service in this configuration.

Scenario 3 – Azure virtual machine needs to resolve a record in an Azure Private DNS Zone.

I’ll now cover DNS resolution of namespaces hosted in Azure Private DNS Zones by compute services running in Azure. There are a number of ways to do this, so I’ll walk through a few of them.

Scenario 3a – Distributed architecture where Azure Private DNS Zones are directly link to each virtual network

One architecture a lot of customers attempt for Azure to Azure resolution is an architecture where the Azure Private DNS Zones are linked directly to each virtual network instead of a common centralized virtual network.

In this architecture each virtual network is configured to use the Azure-provided DNS service via a DNS Server setting on the virtual networks of the 168.63.129.16 virtual IP. The Azure Private DNS Zones are individually linked to each virtual network. Before I get into the reasons why I don’t like this pattern, let me walk through how a query is resolved in this pattern.

- VM2 creates a DNS query for vm1.mydomain.prod.com. VM2 does not have a cached entry for vm1.mydomain.prod.com so the query is passed on to the DNS Server configured for the VMs virtual network interface (VNIC). The DNS Server has been configured by the Azure DHCP Service to the 168.63.129.16 virtual IP which is the default configuration for virtual network DNS Server settings and which passes the query on to the Azure-provided DNS service.

- The recursive query is received by the Azure-provided DNS service and the service determines there is a linked Azure Private DNS Zone for the namespace mydomain.prod.com. The service resolves the hostname and returns the IP.

Alright, why don’t I like this architecture? Well, for multiple reasons:

- There is a limit to the number of virtual networks an Azure Private DNS Zone can be linked to. As I described in my last post, Azure Private DNS Zones should be treated as global resources and you should be using one zone per namespace and linking that zone to virtual networks in multiple regions. If you begin expanding into multiple Azure regions you could run into the limit.

- DNS resolution in this model gets confusing to troubleshoot because you have many links.

So yeah, be aware of those considerations if you end going this route.

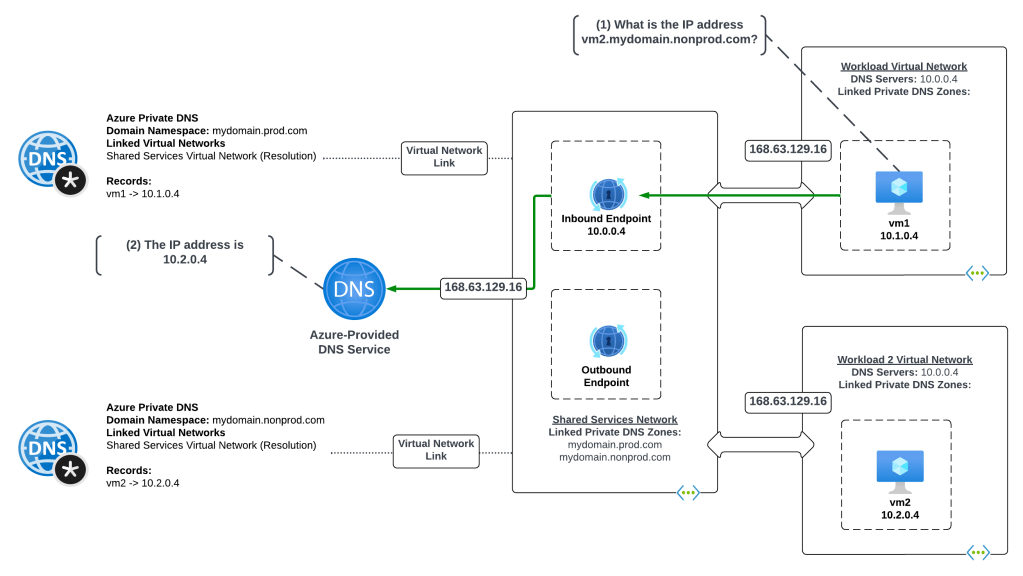

Scenario 3b – Distributed architecture where Azure Private DNS Zones are linked to a central DNS resolution virtual network

This is another alternative for the distributed architecture that can be used if you want to centralize queries to address the considerations of the prior pattern (note that query logging isn’t addressed in the visual below unless you insert a customer-managed DNS service or Azure Firewall instance as I discuss later in this post).

This architecture is somewhat of a combination of a distributed and centralized architecture. All virtual networks in the environment have network connectivity to a shared services virtual network through direct or indirect (such as Azure Virtual WAN or a traditional hub and spoke) virtual network peering. The Resolver and its endpoints are deployed to the shared services virtual network. All Azure Private DNS Zones are linked to the shared services virtual network. A DNS Forwarding Ruleset is linked to each workload virtual network with a single rule forwarding all DNS traffic (except the reserved namespaces covered earlier) to the Resolver inbound endpoint.

Let me walk through a scenario with this architecture where VM1 wants to resolve the IP address for the hostname vm2.mydomain.nonprod.com.

- VM1 creates a DNS query for vm2.mydomain.nonprod.com. VM1 does not have a cached entry for vm2.mydomain.nonprod.com so the query is passed on to the DNS Server configured for the VMs virtual network interface (VNIC). The DNS Server has been configured by the Azure DHCP Service to the 168.63.129.16 virtual IP which is the default configuration for virtual network DNS Server settings and which passes the query on to the Azure-provided DNS service.

- The Azure Private DNS Service checks to see if there is an Azure Private DNS Zone linked to the workload virtual network for the mydomain.nonprod.com domain and validates there is no. The service then checks the linked DNS Forwarding Rule Set linked the virtual network and finds a rule matching the domain pointing queries to the inbound endpoint IP address. The query is passed through the Resolver outbound endpoint to the inbound endpoint and back out the outbound endpoint to the 168.63.129.16 virtual IP address passing the query to the Azure-provided DNS service.

The Azure-provided DNS service checks the shared services virtual network and determines there is a link Azure Private DNS Zone with the name mydomain.nonprod.com. The service resolves the hostname to the IP address and returns the results.

Scenario 3c – Centralized architecture where Azure Private DNS Zones are linked to a central DNS resolution virtual network

This is the more common of the Azure-to-Azure resolution architectures that I come across. Here queries are sent directly to the inbound resolver IP address via the direct or transitive connectivity to the shared services virtual network.

This architecture is centralized architecture where all virtual networks in the environment have network connectivity to a shared services virtual network through direct or indirect (such as Azure Virtual WAN or a traditional hub and spoke) virtual network peering. The Resolver and its endpoints are deployed to the shared services virtual network. All Azure Private DNS Zones are linked to the shared services virtual network. Each workload virtual network is configured with its DNS Server settings to point to the resolver’s inbound endpoint.

Let me walk through the resolution.

- VM1 creates a DNS query for vm2.mydomain.nonprod.com. VM1 does not have a cached entry for vm2.mydomain.nonprod.com so the query is passed on to the DNS Server configured for the VMs virtual network interface (VNIC). The DNS Server has been configured by the Azure DHCP Service to resolver’s inbound endpoint at 10.0.0.4. The query is routed over the virtual network peering to the resolver’s inbound endpoint.

- The inbound endpoint passes the query to the 168.64.129.16 virtual IP and onto the Azure-provided DNS Service. The service determines that an Azure Private DNS Zone named mydomain.nonprod.com is linked to the shared services virtual network. The service then resolves the hostname to the IP address and returns the results.

I’m a fan of this pattern because it’s very simple and easy to understand, which is exactly what DNS should be.

Scenario 4 – Centralized architecture that supports adding DNS query logging (Deprecated)

Now that you have an understanding of the benefits of the Azure Private DNS Resolver, let’s talk about some of the gaps. Prior to July 2025 you couldn’t achieve DNS query logging when using Azure Private DNS Resolver and Azure-provided DNS without the use of an additional server in the middle.

The architecture below was a common way customers addressed the gap when they had plans to eventually move fully into the Private Resolver pattern when it was introduced. DNS Security Policy was introduced in July of 2025 and cleaned up this gap making this architecture unnecessary if the additional DNS Server was solely providing DNS query logging. In this architecture all Azure Private DNS Zones and DNS Forwarding Rule Sets were linked to the shared services virtual network and a customer-managed DNS service is also deployed. All workload virtual networks have connected to the shared service through direct or indirect (Azure Virtual WAN or traditional hub and spoke) virtual network peering. Each workload virtual network has its DNS Server settings configured to use the customer-managed DNS service IP address.

Let me walk through a scenario where VM1 wants to resolve the IP address for a record in an on-premises DNS namespace.

- VM1 creates a DNS query for service.onpremises.com. VM1 does not have a cached entry for service.onpremises.com so the query is passed on to the DNS Server configured for the VMs virtual network interface (VNIC). The DNS Server has been configured by the Azure DHCP Service to the IP address of the customer managed DNS service at 10.1.2.4. The query is passed over the virtual network peering to the customer-managed DNS service.

- The customer-managed DNS service checks its local cache, validates it’s not authoritative for the zone, and passes the query on to its standard forwarder which has been configured to the resolver’s inbound endpoint at 10.1.0.4.

- The inbound endpoint passes the query into the virtual network out the outbound endpoint which passes it on to the 168.63.129.16 virtual IP and onto the Azure-provided DNS service. The Azure-provided DNS service checks the Azure Private DNS Zones linked to the shared services virtual network and determines that no Azure Private DNS Zones with the hostname onpremises.com are linked to it. The DNS Forwarding Rule Set linked to the virtual network is then processed and the matching rule is triggered passing the query out of the outbound endpoint over the ExpressRoute or VPN connection and to the on-premises DNS services.

- The on-premises DNS service checks its local cache and doesn’t find a cached entry. It then checks to see if it is authoritive for the zone, which it is and it resolves the hostname to an IP address and returns the results.

An alternative to using a customer-managed DNS service was using the Azure Firewall DNS proxy service using the pattern documented here.

The primary reason I didn’t remove this architecture completely in my July 2025 update is you’ll still see this architecture in the wild for customers that may not have fully transitioned to DNS Security Policy. Additionally, there may be use cases for using a 3rd-party DNS server to supplement gaps in Azure Private DNS Resolver such as acting as DNS cache or providing advanced DNS features such as virtualized DNS zones.

Summing it up

So yeah, there are a lot of patterns and each one has its own benefits and considerations. My recommendation is for customers to centralize DNS wherever possible because it makes for a fairly simple integration unless you have concerns over hitting QPS. If you have an edge use case for an isolated virtual network, consider the patterns referenced above.

It’s critically important to understand how DNS resolution works from a processing perspective when you have linked Azure Private DNS Zones and DNS Forwarding Rule Sets. The detail is here.

Alexis Plantin put together a great write-up with fancy animated diagrams that put my diagrams to shame. Definitely take a read through his write-up if anything to give him some traffic for creating the animated diagrams. I’m jealous!

There is some good guidance here which talks about considerations for forwarding timeouts when using a third-party DNS server that is forwarding queries to the Azure Private DNS Resolver or to Azure-provided DNS.

Lastly, let me end this with some benefits and considerations of the product.

- Benefits

- No infrastructure to manage. Microsoft is responsible for management of the compute powering the service.

- Unlike Azure-provided DNS alone, it supports conditional forwarding to on-premises.

- Unlike Azure-provided DNS alone, it supports resolution from on-premises to Azure without the need for a DNS proxy.

- Supports multiple patterns for its implementation including centralized and decentralized architectures, even supporting isolated virtual networks.

- DNS query logging can be achieved using DNS Security Policy as of 7/2025.

- Considerations

- The Private DNS Resolver MAY NOT support requests from non-RFC 1918 IP addresses to the inbound endpoint. This was a documented limitation, but has since been removed. However, customers of mine still report it does not work. If you have this use case, your best bet is to try it and open a support ticket if you have issues.

- The Private DNS Resolver DOES NOT support iterative DNS queries. It only supports recursive DNS queries.

- In high volume DNS environments, such as very large VDI deployments, query per second limits could be an issue.

- The Private DNS Resolver does not support authenticated dynamic DNS updates. If you have this use case for a VDI deployment, you will need to use a DNS service that does support it.

Nice Article

Will this pattern work if i want to host a single domain / forest across ?

LikeLike

It should. You would need to setup non-replicating conditional forwarders on the on-premises domain controllers which would point to the domain controllers in Azure. That pattern should work, but there will be the overhead of you remembering to create that conditional forwarder on any newly promoted on-premises domain controllers since it won’t be part of the directory data.

LikeLike

Great article!

But I’m still confused about extending on-prem AD into Azure VM and perhaps adding a few Domain Controllers running in as Azure VM’s.

One hitch I discovered, is that AD domain joined VM’s in Azure don’t register their PTR record in the reverse zone. For instance if you have a 10.0.0.0/24 VNET which has communication down to a data center (VPN/ExpressRoute), all VM’s in that VNET will happily join your on-prem AD and register it’s host record in the forward zone but fails to register it’s PTR record in the reverse zone (0.0.10.in-addr.arpa). Something which is desirable for many reasons.

Reading the docs from MS, Domain Joined VM’s should automatically register their PTR record as part of the join process (Dynamic DNS). But since VM’s are DHCP at the OS NIC level, I assume it shouldn’t work either, or am I wrong?

LikeLike

Great, so glad you got some value out of it!

Where are you hosting the reverse lookup zone? Are you hosting in Azure Private DNS, on your domain controller, or on a third party DNS service like an InfoBlox?

LikeLike

I’m hosting the reverse zone in AD (AD integrated). Since Azure cannot talk to old school AD, reverse DNS have to be hosted in AD. Otherwise we have to manually create reverse records in Private DNS.

LikeLike

Yep, I believe you are correct. I found this reddit thread (https://www.reddit.com/r/networking/comments/73m0sk/azure_dhcp_server_clients_dns_registration/) which seems to cover your use case and confirms your thinking.

LikeLike

Can I not just have BYODNS in shared VNET and configure that DNS IP as primary DNS on all VMs in Spoke VNETs , assuming all these VMs in Spoke VNETs are joined to the same AD domain as the DNS server?

LikeLike

Yes you can and that is actually the pattern I recommend to customers. In that pattern you would place the VMs running your DNS service in a dedicated “shared services VNet” attached to the hub. You would then set the VNet DNS of each VNet to those servers. VMs in the VNets would learn about the servers via the Azure DHCP service. You would then link all Private DNS zones for PrivateLink-exposed services to the shared services VNet and ensure the DNS servers are using the 168 resolver in their VNet as a forwarder.

The only caveat to this pattern is you’ll need a transitive routing solution in the hub to route the traffic from the spoke to the shared services VNet since they aren’t directly peered. This is usually done with whatever firewall you are running in the hub VNet.

LikeLike

Amazing article.

One small observation.

“When configured to use a specific set of DNS servers, a few things happen at the VM. ”

It may benefit to add a separate section doing just Custom DNS without Private DNS Zones.

I observe that in that scenario of just using Custom DNS VM, FQDN would need to be used by members as there is no DNS suffix(only default reddog.microsoft.com).

Further, manual entries(A/CNAME records) would need to be created on custom DNS server for each VM to be resolved.

Both the above can be then solved by using concept of Active Directory:

1.Each VM joined to domain gets a DNS prefix added under settings(as seen under ipconfig /all) —->PQDN can now be used.

2.With active directory, there is no need of manual entry/creation of A records for member VMs.

I am not very sure how the 2nd one works in general(Is it AD thing vs DHCP concept involved vs DNS Server involved) and then how it gets modified to work with Azure(I believe DHCP being handled by Azure at vnet/subnet level and NOT the Domain controller).

Kind regards,

Aditya Garg

LikeLike

Just venturing into Azure VM here.

I have a virtual network gateway setup with IPSec VPN. Installed an Azure VM, and am able to ping the onpremise addresses from it. Now i want this VM to resolve onpremise addresses (and vice versa). Is it required to come up with a new domain name, or can i use the onpremise domain name? And does this new domain name have to be registrered or can it be made up?

LikeLike

Hi Mark.

Since you’ve established connectivity between on-premises and Azure, you can leverage your existing DNS infrastructure on-premises (I’m going to assume you have some) and use that to resolve on-premises machines. Take a look at my article on the Azure Private DNS Resolver (https://journeyofthegeek.com/2022/05/18/a-look-at-the-azure-dns-private-resolver/).

LikeLike

Hello Mark

Impressive article, just curious to know where you found this statement “The Private DNS Resolver DOES NOT support requests from non-RFC 1918 IP addresses to the inbound endpoint” i cannot find it in any Microsoft official documentations.

LikeLike

Hi Tarek. My name is Matt not Mark, but I’ll assume that was a typo. 🙂

That limitation used to be present in public documentation, but was removed. However, that use case still does not work for my customers. If you have this requirement, your best bet is to try it and open a support ticket if you have issues with it.

LikeLike

Hi Matt , apologies for the mixup ! and thanks for the quick response. Now I checked with Microsoft enginèer and he confirmed that this statement was old and was removed since Febrauary this year from public documentations and now non-RFC1918 requests are supported ,and he thankfully tested that and it is working.

LikeLike

Cool! Last I heard from my customers it still doesn’t work but if you can get it working, more power to you!

LikeLike

I just saw your comment at the end “The Private DNS Resolver DOES NOT support iterative DNS queries. It only supports recursive DNS queries.” – this might explain an issue I saw at a customer where their internal corporate DNS was hosting the parent DNS domain and they wanted to delegate sub-domains to Azure DNS. I don’t know all the ins and outs of Azure Private DNS but the delegation was failing with Azure DNS returning a “REFUSED” response code. The only way we could get it working was to set up conditional forwarding for each sub-domain to override the delegation (NS records) and forward the queries to Azure. Configuring forwarders is quite time consuming and creates a brittle configuration but it had the affect of changing the outbound query issued by the corporate DNS from an iterative query to a recursive query, and Azure DNS was then able to respond. I have many years experience configuring DNS that pre-dates Azure and just find their approach rather strange as they create all these issues that wouldn’t exist if they just implemented DNS correctly.

LikeLike

Don’t disagree. The lack of support for iterative queries is a gotcha-based limitation.

LikeLike