This is part of my series on Network Security Perimeters:

- Network Security Perimeters – The Problem They Solve

- Network Security Perimeters – NSP Components

- Network Security Perimeters – NSPs in Action – Key Vault Example

- Network Security Perimeters – NSPs in Action – AI Workload Example

- Network Security Perimeters – NSPs for Troubleshooting

Welcome back to my third post in my NSP (Network Security Perimeter) series. In this post I’m going to start covering some practical use cases for NSPs and demonstrating how they work. I was going to group these use cases in a single post, but it would have been insanely long (and I’m lazy). Instead, I’ll be covering one per post. These use cases are likely scenarios you’ve run into and do a good job demonstrating the actual functionality.

A Quick Review

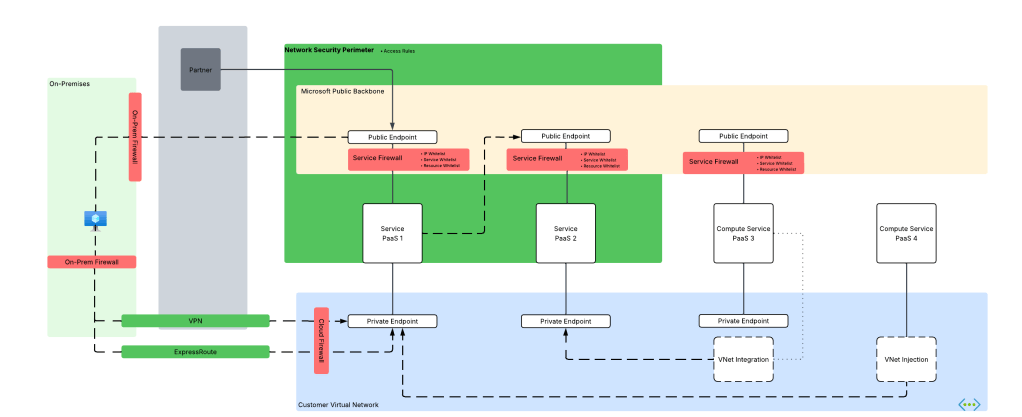

In my first post I broke PaaS services into compute-based PaaS and service-based PaaS. NSPs are focused on solving problems for service-based PaaS. These problems include a lack of outbound network controls to mitigate data exfiltration, inconsistent offerings for inbound network controls across PaaS services, scalability with inbound IP whitelisting, difficulty configuring and managing these controls at scale, and inconsistent quality of logs across services for simple fields you’d expect in a log like calling inbound IP address.

My second post walked through the components that make up a Network Security Perimeter and their relationships to each other. I walked through each of the key components including the Network Security Perimeter, profiles, access policies, and resource associations. If you haven’t read that post, you need to read it before you tackle this one. My focus in this post will be where those resources are used and will assume you grasp their function and relationships.

With that refresher out of the way, let’s get to the good stuff.

Use Case 1: Securing Azure Key Vaults

Azure Key Vault is Microsoft’s native PaaS offering for secure key, secret, and certificate storage. Secrets sometimes need to be accessed by Microsoft SaaS (software-as-a-service) and compute-based PaaS that do not support virtual network injection or a managed virtual network concept, such as some use cases for PowerBI. Vaults are used by 3rd-party products outside of Azure or from another CSP (cloud service provider). There are also use cases where a customer may be new to Azure and doesn’t yet have the necessary hybrid connectivity and Private DNS configuration to support the usage of Private Endpoints. In these scenarios, Private Endpoints are not an option and the traffic needs to come in the public endpoint of the vault. Here is our use case for NSPs.

Historically, folks would try to solve this with IP whitelisting on the Key Vault service firewall. As I covered in my first post, this is a localized configuration to the resource and can be mucked with by the resource owner unless permissions are properly scoped or an Azure Policy is used to enforce a specific configuration. This makes it difficult to put network control in the hands of security while leaving the rest of the configuration of the resource to the resource owner. Another issue that sometimes pops up with this pattern is hitting the maximum of 400 prefixes for the service firewall rules.

NSPs provide us with a few advantages here:

- Network security can be controlled by the NSP and that NSP can be controlled by the security team while leaving the rest of the resource configuration to the resource owner.

- You can allow more than 400 inbound IP rules (up to 500 in my testing). Sometimes a few extra IP prefixes is all you needed back with the service firewall.

In this type of use case, we could do something like the below. Here we have a single Network Security Perimeter for our two categories of Key Vaults for a product line. Category 1 Key Vaults need to be accessed by 3rd-party SaaS and applications that do not have the necessary network path to use Private Endpoints. Category 2 are Key Vaults used by internally facing application within Azure and those Key Vaults need to be restricted to a Private Endpoint.

Public Key Vault

For this scenario we can build something like in the image above where we have a single NSP with two profiles. One profile will be used by our “public” Key Vaults. This profile will be associated with an access rule that allows a set of trusted IP addresses from a 3rd-party SaaS solution. The other profile will have no associated access rules, thus blocking all access to the Key Vault over the public endpoint. Both resource associations will be set to enforced to ensure the the NSP rules override the local service firewall rules.

Let’s take a look at this in action.

For this scenario, I have an NSP design setup exactly as above. The access rule applied to my public vault has the IP address of my machine as seen below:

At this point my vault isn’t associated with the NSP yet and it has been configured to allow all public network access. Attempts at accessing the vault from a random public IP shows successful as would be expected.

Next I associate the vault to the NSP and set it to enforced mode. By default it will be configured in Transition mode (see my second post for detail on this) which means it will log whether the traffic would be allowed or denied but it won’t block the traffic. Since I want the NSP to override the local service firewall, I’m going to set it to enforced.

When trying to pull the secret from the vault using a machine with the trusted public IP listed in the access rule associated to the profile, I’m capable of getting the secret.

If I attempt to access the secret from an untrusted IP, even with the service firewall on the vault configured to allow all public network access, I’m rejected with the message below.

Review of the logs (NSPAccessLogs table) shows that the successful call was due to the access rule I put in place and the denied call triggered DefaultDenyAll rule.

Now what about my private vault? Let’s take a look at that one next.

Private Key Vault

For this scenario I’m going to use the second profile in the NSP. This profile doesn’t have any associated access rules which effectively blocks all traffic to the public endpoint originating from outside the NSP. My goal is to make this vault accessible only from a private endpoint.

First, I associate the resource to the NSP profile and configure it in enforced mode.

This is another vault where I’ve configured the service firewall to allow all public network access. Attempting to access the resource throws the message indicating the NSP is blocking access.

I’ve created a Private Endpoint for this vault as well. As I covered earlier in this series, NSPs are focused on public access and do not limit Private Endpoint access, so that means it doesn’t log access from a Private Endpoint, right? Wrong! A neat feature of NSP wrapped resources is those the NSPs will allow the traffic and log it as seen below.

In the above log entry you’ll see the traffic is labeled as private indicating it’s traffic being allowed through the DefaultAllowAll rule and the TrafficType set to Private because it’s coming in through a Private Endpoint. Interestingly enough, you also get the operation that was being performed in the request. I could have sworn these logs used to include the specific Private Endpoint resource ID the traffic ingressed from, but perhaps I imagined that or it was removed when the service graduated to GA (generally available).

Summing it up

In this post I gave an overview of a simple use case that many folks may have today. You could easily sub out Key Vault for any of the other supported PaaS that has a similar public endpoint access model and the setup will be the same. Here are some key takeaways:

- NSPs allow you to enforce public access network controls regardless how the resource owner configures the service firewall on the resource.

- Profiles seem to support a maximum of 500 IP prefixes for inbound and 500 for outbound. This is more than the 400 available in the service firewall. This is based on my testing and no idea if it’s a soft or hard limit.

- NSPs provide a standardized log format for network access. No more looking at 30 different log schemas across different resources, half of which don’t contain network information or someone drank too much tequila and decided to mask an octet of the IP. Additionally, they will log network access attempts through Private Endpoints.

In my next post I’ll cover a use where we have two resources in the same NSP that communicate with each other.

See you next post!