This is part of my series on GenAI Services in Azure:

- Azure OpenAI Service – Infra and Security Stuff

- Azure OpenAI Service – Authentication

- Azure OpenAI Service – Authorization

- Azure OpenAI Service – Logging

- Azure OpenAI Service – Azure API Management and Entra ID

- Azure OpenAI Service – Granular Chargebacks

- Azure OpenAI Service – Load Balancing

- Azure OpenAI Service – Blocking API Key Access

- Azure OpenAI Service – Securing Azure OpenAI Studio

- Azure OpenAI Service – Challenge of Logging Streaming ChatCompletions

- Azure OpenAI Service – How To Get Insights By Collecting Logging Data

- Azure OpenAI Service – How To Handle Rate Limiting

- Azure OpenAI Service – Tracking Token Usage with APIM

- Azure AI Studio – Chat Playground and APIM

- Azure OpenAI Service – Streaming ChatCompletions and Token Consumption Tracking

- Azure OpenAI Service – Load Testing

Hello folks! I’m back again with another post on the Azure OpenAI Service. I’ve been working with a number of Microsoft customers in regulated industries helping to get the service up and running in their environments. A question that frequently comes up in this conversations is “How do I prevent usage of the API keys?”. Today, I’m going to cover this topic.

I’ve covered authentication in the AOAI (Azure OpenAI Service) in a past post so read that if you need the gory details. For the purposes of this post, you need to understand that AOIA supports both API keys and AAD (Azure Active Directory) authentication. This dual support is similar to other Azure PaaS (platform-as-a-service) offerings such as Azure Storage, Azure CosmosDB, and Azure Search. When the AOAI instance is created, two API keys are generated which provide full permissions at the data plane. If you’re unfamiliar with the data plane versus management plane, check out my post on authorization.

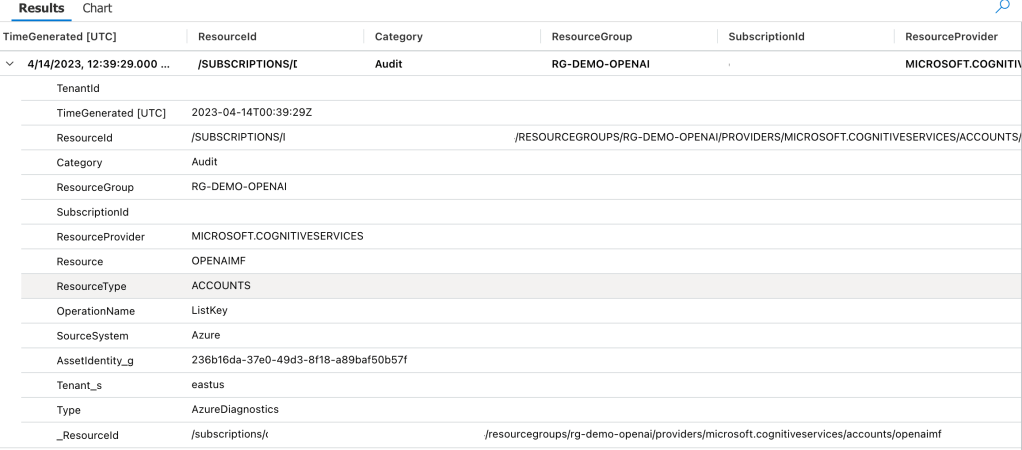

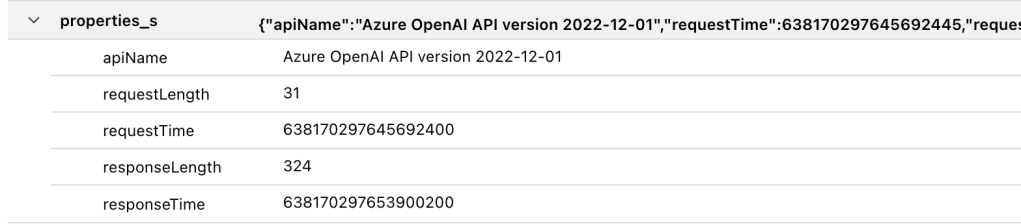

Given the API keys provide full permissions at the data plane monitoring and controlling their access is critical. As seen in my logging post monitoring the usage of these keys is no simple task since the built-in logging is minimal today. You could use a custom APIM (Azure API Management) policy to include a portion of the API key to track its usage if you’re using the advanced logging pattern, but you still don’t have any ability to restrict what the person/application can do within the data plane like you can when using AAD authentication and authorization. You should prefer AAD authentication and authorization where possible and tightly control API key usage.

In my authorization and logging posts I covered how to control and track who gets access to the API keys. I’ve also covered how APIM can be placed in front of an AOAI instance to enforce AAD authentication. If you block network access to the AOAI service to anything but APIM (such as using a Private Endpoint and Network Security Group) you force the usage of APIM which forces the use of AAD authentication preventing API keys from being used.

The major consideration of the pattern above is it breaks the Azure OpenAI Studio as of today (this may change in the future). The Azure OpenAI Studio is an GUI-based application available within the Azure Portal which allows for simple point-and-click actions within the AOAI data plane. This includes actions such as deploying models and sending prompts to a model through a GUI interface. While all this is available via API calls, you will likely have a user base that wants access a simple GUI to perform these types of actions without having to code to them. To work around this limitation you have to open up network access from the user’s endpoint to the AOAI instance. Opening up these network flows allows the user to bypass APIM which means the user could use an API key to make calls to the AOAI service. So what to do?

In every solution in tech (and life) there is a screwdriver and a hammer. While the screwdriver is the optimal way to go, sometimes you need the hammer. With AOAI the hammer solution is to block usage of API key-based authentication at the AOAI instance level. Since AOAI exists under the Azure Cognitive Services framework, it benefits from a poorly documented property called disableLocalAuth. Setting this property to true blocks the API key-based authentication completely. This property can be set at creation or after the AOAI instance has been deployed. You can set it via PowerShell or via a REST call. Below is code demonstrating how to set it using a call to the Azure REST API.

body=$(cat <<EOF

{

"properties" : {

"disableLocalAuth": true

}

}

az rest --method patch --uri "https://management.azure.com/subscriptions/SUBSCRIPTION_ID/resourceGroups/RESOURCE_GROUP/providers/Microsoft.CognitiveServices/accounts/AOAI_INSTANCE_NAME?api-version=2021-10-01" --body $body The AOIA instance will take about 2-5 minutes to update. Once the instance finishes updating, all calls to it using API key-based authentication will receive an error such as seen below when using the OpenAI Python SDK.

You can re-enable the usage of API keys by setting the property back to false. Doing this will update the AOAI resource again (around 2-5 minutes) and the instance will begin accepting API keys. Take note that turning the setting off and then back on again WILL cycle the API keys so don’t go testing this if you have applications in production using API keys today.

Mission accomplished right? The user or application can only access the AOAI instance using AAD authentication which enforced granular Azure RBAC authroization. Heck, there is even an Azure Policy available you can use to audit whether AOAI instances have had this property set.

There is a major consideration with the above method. While you’ve blocked access to the API keys, you’re still created a way to circumvent APIM. This means you lose out on the advanced logging provided by APIM and you’ll have to live with the native logging. You’ll need to determine whether that risk is acceptable to your organization.

My suggestion would be to use this control in combination with strict authorization and network controls. There should be a very limited set of users with permissions directly on the AOAI resource and the direct network access to the resource should be tightly controlled. The network control could be accomplished by creating a shared jump host users that require this access could use. Key thing is you treat access to the Azure OpenAI Studio as an exception versus the norm. I’d imagine Microsoft will evolve the Azure OpenAI Studio deployment options over time and address the gaps in native logging. For today, this provides a reasonable compromise.

I did encounter one “quirk” with this option that is worth noting. The account I used to lab this all out had the Owner role assignment at the subscription level. With this account I was able to do whatever I wanted within the AOAI data layer when disableLocalAuth was set to false. When I set disableLocalAuth to true I was unable to make data plane calls (such as deploying new models). When I granted my user one of the data plane roles (such as Azure Cognitive Service OpenAI Contributor) I was able to perform data plane operations once again. It seems like setting this property to true enforces a rule which requires being granted specific data plane-level permissions. Make sure you understand this before you modify the property.

Well folks that concludes this blog post. Here are your key takeaways:

- API Key-based authentication can be blocked at the AOIA instance by setting the disableLocalAuth property to true. This setting can be set at deployment or post deployment and takes 2-5 minutes to take effect. Switching the value of this property from true to false will regenerate the API keys for the instance.

- The Azure OpenAI Studio requires the user’s endpoint have direct network access to the AOAI instance. This is because it uses the user’s endpoint to make specific API calls to the data plane. You can look at this yourself using debug mode in your browser or a local proxy like Fiddler. Direct network access to the AOAI instance means you will only have the information located in the native logs for the activities the user performs.

- Setting disableLocalAuth to true enforces a requirement to have specific data plane-level permissions. Owner on the subscription or resource group is not sufficient. Ensure you pre-provision your users or applications who require access to the AOAI instance with the built-in Azure RBAC roles such as Azure Cognitive Services OpenAI User or a custom role with equivalent permissions prior to setting the option to true.

Thanks folks and have a great weekend!