This is part of my series on the Azure OpenAI Service:

- Azure OpenAI Service – Infra and Security Stuff

- Azure OpenAI Service – Authentication

- Azure OpenAI Service – Authorization

- Azure OpenAI Service – Logging

- Azure OpenAI Service – Azure API Management and Entra ID

- Azure OpenAI Service – Granular Chargebacks

- Azure OpenAI Service – Load Balancing

- Azure OpenAI Service – Blocking API Key Access

- Azure OpenAI Service – Securing Azure OpenAI Studio

- Azure OpenAI Service – Challenge of Logging Streaming ChatCompletions

- Azure OpenAI Service – How To Get Insights By Collecting Logging Data

- Azure OpenAI Service – How To Handle Rate Limiting

- Azure OpenAI Service – Tracking Token Usage with APIM

- Azure AI Studio – Chat Playground and APIM

- Azure OpenAI Service – Streaming ChatCompletions and Token Consumption Tracking

- Azure OpenAI Service – Load Testing

Updates:

- 1/18/2024 to reference considerable library changes with new API version. See below for details

- 4/3/2023 with simpler way to authenticate with Azure AD via Python SDK

Hello again!

1/18/2024 Update – Hi folks! There were some considerable changes to the OpenAI Python SDK which offers an even simpler integration with the Azure OpenAI Service. While the code in this post is a bit dated, I feel the thought process is still important so I’m going to preserve it as is! If you’re looking for examples of how to authenticate with the Azure OpenAI Service using the Python SDK with different types of authentication (service principal vs managed identity) or using the REST API, I’ve placed a few examples in this GitHub repository. Hope it helps!

Days and nights have been busy diving deeper into the AI landscape. I’ve been reading a great book by Tom Taulli called Artificial Intelligence Basics: A Non-Technical Introduction. It’s been a huge help in getting down the vocabulary and understanding the background to the technology from the 1950s on. In combination with the book, I’ve been messing around a lot with Azure’s OpenAI Service and looking closely at the infrastructure and security aspects of the service.

In my last post I covered the controls available to customers to secure their specific instance of the service. I noted that authentication to the service could be accomplished using Azure Active Directory (AAD) authentication. In this post I’m going to take a deeper look at that. Be ready to put your geek hat on because this post will be getting down and dirty into the code and HTTP transactions. Let’s get to it!

Before I get into the details of how supports AAD authentication, I want to go over the concepts of management plane and data plane. Think of management plane for administration of the resource and data plane for administration of the data hosted within the resource. Many services in Azure have separate management planes and data planes. One such service is Azure Storage which just so happens to have similarities with authentication to the OpenAI Service.

When a customer creates an Azure Storage Account they do this through interaction with the management plane which is reached through the ARM API hosted behind management.azure.come endpoint. They must authenticate against AAD to get an access token to access the API. Authorization via Azure RBAC then takes place to validate the user, managed identity, or service principal has permissions on the resource. Once the storage account is created, the customer could modify the encryption key from a platform managed key (PMK aka key managed by Microsoft) to a customer managed key (CMK), enable soft delete, or enable network controls such as the storage firewall. These are all operations against the resource.

Once the customer is ready to upload blob data to the storage account, they will do this through a data plane operation. This is done through the Blob Service API. This API is hosted behind the blob.core.windows.net endpoint and operations include creation of a blob or deletion of a blob. To interact with this API the customer has two means of authentication. The first method is the older method of the two and involves the use of static keys called storage account access keys. Every storage account gets two of these keys when a storage account is provisioned. Used directly, these keys grant full access to all operations and all data hosted within the storage account (SAS tokens can be used to limit the operations, time, and scope of access but that won’t be relevant when we talk the OpenAI service). Not ideal right? The second method is the recommended method and that involves AAD authentication. Here the security principal authenticates to AAD, receives an access token, and is then authorized for the operation via Azure RBAC. Remember, these are operations against the data hosted within the resource.

Now why did I give you a 101 on Azure Storage authentication? Well, because the Azure OpenAI Service works in a very similar way.

Let’s first talk about the management plane of the Azure OpenAI Service. Like Azure Storage (and the rest of Azure’s services) it is administered through the ARM API behind the management.azure.com endpoint. Customers will use the management plane when they want to create an instance of the Azure OpenAI Service, switch it from a PMK to CMK, or setup diagnostic settings to redirect logs (I’ll cover logging in a future post). All of these operations will require authentication to AAD and authorization via Azure RBAC (I’ll cover authorization in a future post).

Simple right? Now let’s move to the complexity of the data plane.

Two API keys are created whenever a customer creates an Azure OpenAI Service instance. These API keys allow the customer full access to all data plane operations. These operations include managing a deployment of a model, managing training data that has been uploaded to the service instance and used to fine tune a model, managing fine tuned models, and listing available models. These operations are performed against the Azure OpenAI Service API which lives behind a unique label with an FQDN of openai.azure.com (such as myservice.openai.azure.com). Pretty much all the stuff you would be doing through the Azure OpenAI Studio. If you opt to use these keys you’ll need to remember control access to these keys via securing management plane authorization aka Azure RBAC.

In the above image I am given the option to regenerate the keys in the case of compromise or to comply with my organization’s key rotation process. Two keys are provided to allow for continued access to the service while other key is being rotated.

Here I have simple bit of code using the OpenAI Python SDK. In the code I provide a prompt to the model and ask it to complete it for me and use one of the API keys to authenticate to it.

import logging

import sys

import os

import openai

def main():

# Setup logging

try:

logging.basicConfig(

level=logging.ERROR,

format='%asctime)s - %(name)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s',

handlers=[logging.StreamHandler(sys.stdout)]

)

except:

logging.error('Failed to setup logging: ', exc_info=True)

try:

# Setup OpenAI Variables

openai.api_type = "azure"

openai.api_base = os.getenv('OPENAI_API_BASE')

openai.api_version = "2022-12-01"

openai.api_key = os.getenv('OPENAI_API_KEY')

response = openai.Completion.create(

engine=os.getenv('DEPLOYMENT_NAME'),

prompt='Once upon a time'

)

print(response.choices[0].text)

except:

logging.error('Failed to respond to prompt: ', exc_info=True)

if __name__ == "__main__":

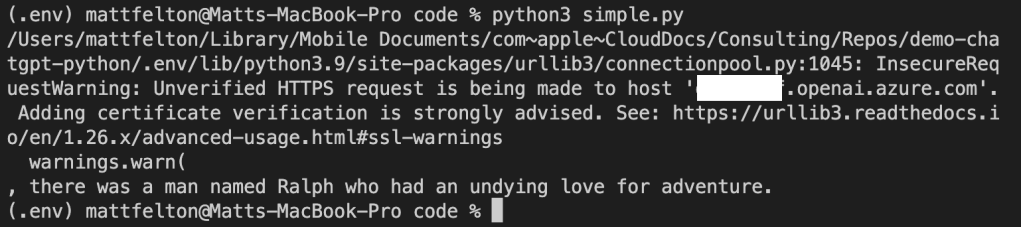

main()The model gets creative and provides me with the response below.

If you look closely you’ll notice an warning about the security of my session. The reason I’m getting that error is shut off certificate verification in the OpenAI library in order to intercept the calls with Fiddler. Now let me tell you, shutting off certificate verification was a pain in the ass because the developers of the SDK are trying to protect users from the bad guys. Long story short, the Azure Python SDK doesn’t provide an option to turn off certificate checking like say the Azure Python SDK (which you can pass a kwarg of verify=False to turn it off in the request library used underneath). While the developers do provide a property called verify_ssl_certs, it doesn’t actually do anything. Since most Python SDKs use the requests library underneath the hood, I went through the library on my machine and found the api_requestor.py file. Within this file I modified the _make_session function which is creating a requests Sessions object. Here I commented out the developers code and added the verify=False property to the Session object being created.

Now don’t go and do this in any environment that matters. If you’re getting a certificate verification failure in your environment you should be notifying your information security team. Certificate verification is an absolute must to ensure the identity of the upstream server and to mitigate the risk of man-in-the-middle attacks.

Once I was able to place Fiddler in the middle of the HTTPS session I was able to capture the conversation. In the screenshot below, you can see the SDK passing the api-key header. Take note of that header name because it will become relevant when we talk AAD authentication. If you’re using OpenAI’s service already, then this should look very familiar to you. Microsoft was nice enough to support the existing SDKs when using one of the API keys.

At this point you’re probably thinking, “That’s all well and good Matt, but I want to use AAD authentication for all the security benefits AAD provides over a static key.” Yeah yeah, I’m getting there. You can’t blame me for nerding out a bit with Fiddler now can you?

Alright, so let’s now talk AAD authentication to the data plane of the Azure OpenAI Service. Possible? Yes, but with some caveats. The public documentation illustrates an example of how to do this using curl. However, curl is great for a demonstration of a concept, but much more likely you’ll be using an SDK for your preferred programming language. Since Python is really the only programming language I know (PowerShell doesn’t count and I don’t want to show my age by acknowledging I know some Perl) let me demonstrate this process using our favorite AAD SDK, MSAL.

For this example I’m going to use a service principal, but if your code is running in Azure you should be using a managed identity. When creating the service principal I granted it the Cognitive Services User RBAC role on the resource group containing the Azure OpenAI Service instance as suggested in the documentation. This is required to authorize the service principal access to data plane operations. There are a few other RBAC roles for the service, but as I said earlier, I’ll cover authorization in a future post. Once the service principal was created and assigned the appropriate RBAC role, I modified my code to include a function which calls MSAL to retrieve an access token with the access scope of Cognitive Services, which the Azure OpenAI Service falls under. I then pass that token as the API key in my call to the Azure OpenAI Service API.

import logging

import sys

import os

import openai

from msal import ConfidentialClientApplication

def get_sp_access_token(client_id, client_credential, tenant_name, scopes):

logging.info('Attempting to obtain an access token...')

result = None

print(tenant_name)

app = ConfidentialClientApplication(

client_id=client_id,

client_credential=client_credential,

authority=f"https://login.microsoftonline.com/{tenant_name}",

)

result = app.acquire_token_for_client(scopes=scopes)

if "access_token" in result:

logging.info('Access token successfully acquired')

return result['access_token']

else:

logging.error('Unable to obtain access token')

logging.error(f"Error was: {result['error']}")

logging.error(f"Error description was: {result['error_description']}")

logging.error(f"Error correlation_id was: {result['correlation_id']}")

raise Exception('Failed to obtain access token')

def main():

# Setup logging

try:

logging.basicConfig(

level=logging.ERROR,

format='%asctime)s - %(name)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s',

handlers=[logging.StreamHandler(sys.stdout)]

)

except:

logging.error('Failed to setup logging: ', exc_info=True)

try:

# Obtain an access token

token = get_sp_access_token(

client_id = os.getenv('CLIENT_ID'),

client_credential = os.getenv('CLIENT_SECRET'),

tenant_name = os.getenv('TENANT_ID'),

scopes = "https://cognitiveservices.azure.com/.default"

)

except:

logging.error('Failed to obtain access token: ', exc_info=True)

try:

# Setup OpenAI Variables

openai.api_type = "azure"

openai.api_base = os.getenv('OPENAI_API_BASE')

openai.api_version = "2022-12-01"

openai.api_key = token

response = openai.Completion.create(

engine=os.getenv('DEPLOYMENT_NAME'),

prompt='Once upon a time'

)

print(response.choices[0].text)

except:

logging.error('Failed to summarize file: ', exc_info=True)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()Let’s try executing that and see what happens.

Uh-oh! What happened? If you recall from earlier the API key is passed in the api-key header. However, to use the access token provided by AAD we have to pass it in the authorization header as seen in the example in Microsoft public documentation.

curl ${endpoint%/}/openai/deployments/YOUR_DEPLOYMENT_NAME/completions?api-version=2022-12-01 \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-H "Authorization: Bearer $accessToken" \

-d '{ "prompt": "Once upon a time" }'Thankfully there is a solution to this one without requiring you to modify the OpenAI SDK. If you take a look in the api_requestor.py file again in the library you will see it provides the ability to override the headers passed in the request.

With this in mind, I made a few small modifications. I removed the api_key property and added an Authorization header to the request to the Azure OpenAI Service API which includes the access token received back from AAD.

import logging

import sys

import os

import openai

from msal import ConfidentialClientApplication

def get_sp_access_token(client_id, client_credential, tenant_name, scopes):

logging.info('Attempting to obtain an access token...')

result = None

print(tenant_name)

app = ConfidentialClientApplication(

client_id=client_id,

client_credential=client_credential,

authority=f"https://login.microsoftonline.com/{tenant_name}",

)

result = app.acquire_token_for_client(scopes=scopes)

if "access_token" in result:

logging.info('Access token successfully acquired')

return result['access_token']

else:

logging.error('Unable to obtain access token')

logging.error(f"Error was: {result['error']}")

logging.error(f"Error description was: {result['error_description']}")

logging.error(f"Error correlation_id was: {result['correlation_id']}")

raise Exception('Failed to obtain access token')

def main():

# Setup logging

try:

logging.basicConfig(

level=logging.ERROR,

format='%asctime)s - %(name)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s',

handlers=[logging.StreamHandler(sys.stdout)]

)

except:

logging.error('Failed to setup logging: ', exc_info=True)

try:

# Obtain an access token

token = get_sp_access_token(

client_id = os.getenv('CLIENT_ID'),

client_credential = os.getenv('CLIENT_SECRET'),

tenant_name = os.getenv('TENANT_ID'),

scopes = "https://cognitiveservices.azure.com/.default"

)

except:

logging.error('Failed to obtain access token: ', exc_info=True)

try:

# Setup OpenAI Variables

openai.api_type = "azure"

openai.api_base = os.getenv('OPENAI_API_BASE')

openai.api_version = "2022-12-01"

response = openai.Completion.create(

engine=os.getenv('DEPLOYMENT_NAME'),

prompt='Once upon a time',

headers={

'Authorization': f'Bearer {token}'

}

)

print(response.choices[0].text)

except:

logging.error('Failed to summarize file: ', exc_info=True)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()Running the code results in success!

4/3/2023 Update – Poking around today looking at another aspect of the service, I came across this documentation on an even simpler way to authenticate with Azure AD without having to use an override. In the code below, I specify an openai.api_type of azure_ad which allows me to pass the token direct via the openai_api_key property versus having to pass a custom header. Definitely a bit easier!

import logging

import sys

import os

import openai

from msal import ConfidentialClientApplication

def get_sp_access_token(client_id, client_credential, tenant_name, scopes):

logging.info('Attempting to obtain an access token...')

result = None

print(tenant_name)

app = ConfidentialClientApplication(

client_id=client_id,

client_credential=client_credential,

authority=f"https://login.microsoftonline.com/{tenant_name}",

)

result = app.acquire_token_for_client(scopes=scopes)

if "access_token" in result:

logging.info('Access token successfully acquired')

return result['access_token']

else:

logging.error('Unable to obtain access token')

logging.error(f"Error was: {result['error']}")

logging.error(f"Error description was: {result['error_description']}")

logging.error(f"Error correlation_id was: {result['correlation_id']}")

raise Exception('Failed to obtain access token')

def main():

# Setup logging

try:

logging.basicConfig(

level=logging.ERROR,

format='%asctime)s - %(name)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s',

handlers=[logging.StreamHandler(sys.stdout)]

)

except:

logging.error('Failed to setup logging: ', exc_info=True)

try:

# Obtain an access token

token = get_sp_access_token(

client_id = os.getenv('CLIENT_ID'),

client_credential = os.getenv('CLIENT_SECRET'),

tenant_name = os.getenv('TENANT_ID'),

scopes = "https://cognitiveservices.azure.com/.default"

)

print(token)

except:

logging.error('Failed to obtain access token: ', exc_info=True)

try:

# Setup OpenAI Variables

openai.api_type = "azure_ad"

openai.api_base = os.getenv('OPENAI_API_BASE')

openai.api_key = token

openai.api_version = "2022-12-01"

response = openai.Completion.create(

engine=os.getenv('DEPLOYMENT_NAME'),

prompt='Once upon a time '

)

print(response.choices[0].text)

except:

logging.error('Failed to summarize file: ', exc_info=True)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()Let me act like I’m ChatGPT and provide you a summary of what we learned today.

- The Azure OpenAI Service has both a management plane and data plane.

- The Azure OpenAI Service data plane supports two methods of authentication which include static API keys and Azure AD.

- The static API keys provide full permissions on data plane operations. These keys should be rotated in compliance with organizational key rotation policies.

- The OpenAI SDK for Python (and I’m going to assume the others) sends an api-key header by default. This behavior can be overridden to send an Authorization header which includes an access token obtained from Azure AD.

- It’s recommended you use Azure AD authentication where possible to leverage all the bells and whistles of Azure AD including the usage of managed identities, improved logging, and conditional access for service principal-based access.

Well folks, that concludes this post. I’ll be uploading the code sample above to my GitHub later this week. In the next batch of posts I’ll cover the authorization and logging aspects of the service.

I hope you got some value and good luck in your AI journey!

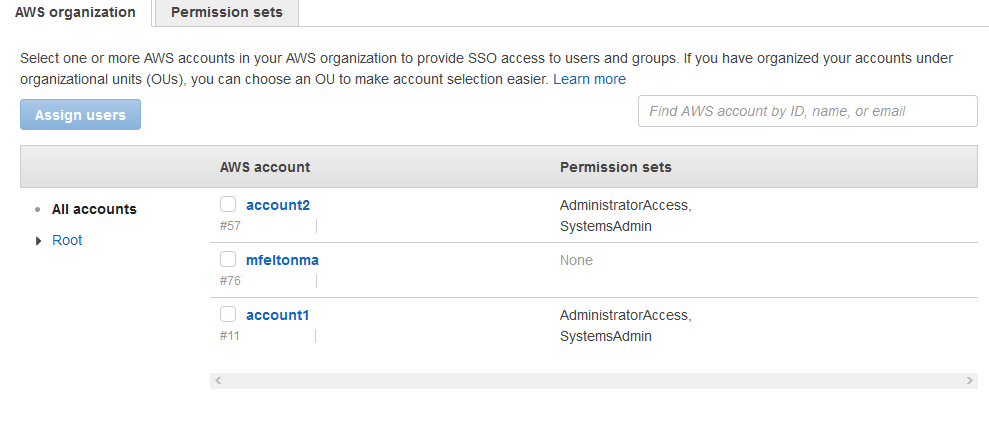

The permission sets tab displays the permission sets I’ve created and whether or not they’ve been provisioned to any accounts. In the screenshot below you’ll see I’ve added four AWS-managed policies for Billing, SecurityAudit, AdministratorAccess, and NetworkAdministrator. Additionally, I created a new permission set named SystemsAdmin which uses a custom IAM policy which restricts the principal assuming the rule to EC2, CloudWatch, and ELB activities.

The permission sets tab displays the permission sets I’ve created and whether or not they’ve been provisioned to any accounts. In the screenshot below you’ll see I’ve added four AWS-managed policies for Billing, SecurityAudit, AdministratorAccess, and NetworkAdministrator. Additionally, I created a new permission set named SystemsAdmin which uses a custom IAM policy which restricts the principal assuming the rule to EC2, CloudWatch, and ELB activities.