Welcome back. Today I will be wrapping up my deep dive into Azure AD Pass-through authentication. If you haven’t already, take a read through part 1 for a background into the feature. Now let’s get to the good stuff.

I used a variety of tools to dig into the feature. Many of you will be familiar with the Sysinternals tools, WireShark, and Fiddler. The Rohitab API Monitor. This tool is extremely fun if you enjoy digging into the weeds of the libraries a process uses, the methods it calls, and the inputs and outputs. It’s a bit buggy, but check it out and give it a go.

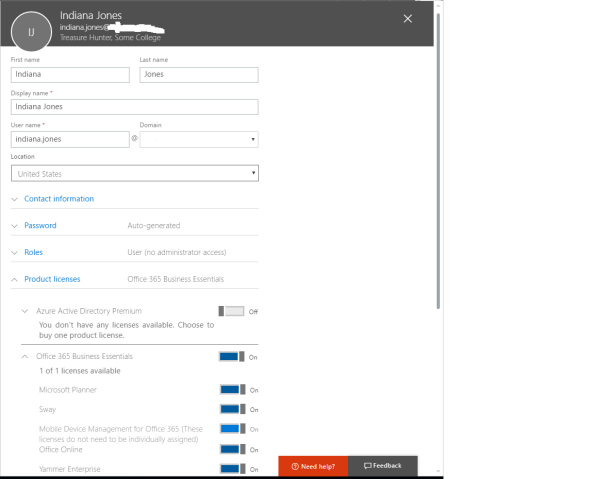

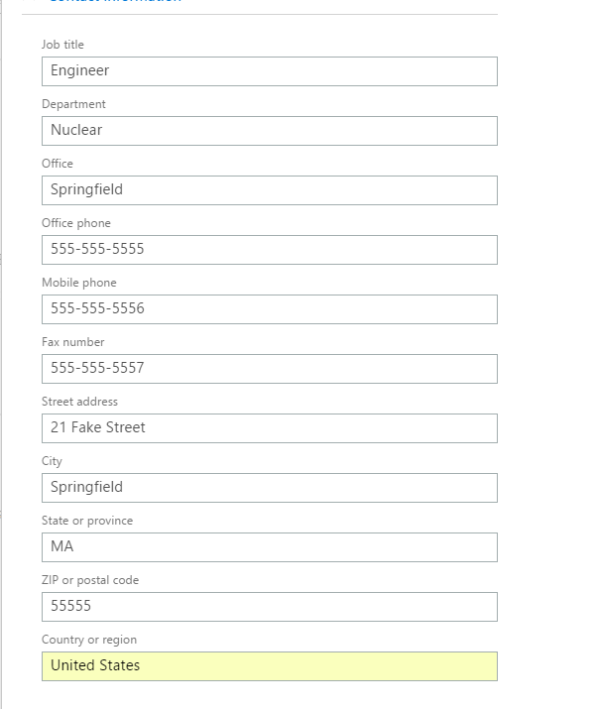

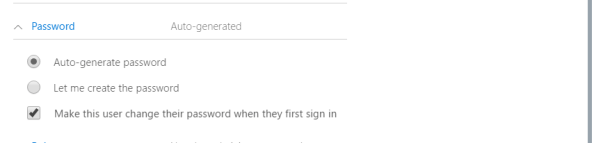

As per usual, I built up a small lab in Azure with two Windows Server 2016 servers, one running AD DS and one running Azure AD Connect. When I installed Azure AD Connect I configured it to use pass-through authentication and to not synchronize the password. The selection of this option will the MS Azure Active Directory Application Proxy. A client certificate will also be issued to the server and is stored in the Computer Certificate store.

In order to capture the conversations and the API calls from the MS Azure Active Directory Application Proxy (ApplicationProxyConnectorService.exe) I set the service to run as SYSTEM. I then used PSEXEC to start both Fiddler and the API Monitor as SYSTEM as well. Keep in mind there is mutual authentication occurring during some of these steps between the ApplicationProxyConnectorService.exe and Azure, so the public-key client certificate will need to be copied to the following directories:

- C:WindowsSysWOW64configsystemprofileDocumentsFiddler2

- C:WindowsSystem32configsystemprofileDocumentsFiddler2

So with the basics of the configuration outlined, let’s cover what happens when the ApplicationProxyConnectorService.exe process is started.

- Using WireShark I observed the following DNS queries looking for an IP in order to connect to an endpoint for the bootstrap process of the MS AAD Application Proxy.DNS Query for TENANT ID.bootstrap.msappproxy.net

DNS Response with CNAME of cwap-nam1-runtime.msappproxy.net

DNS Response with CNAME of cwap-nam1-runtime-main-new.trafficmanager.net

DNS Response with CNAME of cwap-cu-2.cloudapp.net

DNS Response with A record of an IP - Within Fiddler I observed the MS AAD Application Proxy establishing a connection to TENANT_ID.bootstrap.msappproxy.net over port 8080. It sets up a TLS 1.0 (yes TLS 1.0, tsk tsk Microsoft) session with mutual authentication. The client certificate that is used for authentication of the MS AAD Application Proxy is the certificate I mentioned above.

- Fiddler next displayed the MS AAD Application Proxy doing an HTTP POST of the XML content below to the ConnectorBootstrap URI. The key pieces of information provided here are the ConnectorID, MachineName, and SubscriptionID information. My best guess MS consumes this information to determine which URI to redirect the connector to and consumes some of the response information for telemetry purposes.

- Fiddler continues to provide details into the bootstrapping process. The MS AAD Application Proxy receives back the XML content provided below and a HTTP 307 Redirect to bootstrap.his.msappproxy.net:8080. My guess here is the process consumes this information to configure itself in preparation for interaction with the Azure Service Bus.

- WireShark captured the DNS queries below resolving the IP for the host the process was redirected to in the previous step.DNS Query for bootstrap.his.msappproxy.net

DNS Response with CNAME of his-nam1-runtime-main.trafficmanager.net

DNS Response with CNAME of his-eus-1.cloudapp.net

DNS Response with A record of 104.211.32.215 - Back to Fiddler I observed the connection to bootstrap.his.msappproxy.net over port 8080 and setup of a TLS 1.0 session with mutual authentication using the client certificate again. The process does an HTTP POST of the XML content below to the URI of ConnectorBootstrap?his_su=NAM1. More than likely this his_su variable was determined from the initial bootstrap to the tenant ID endpoint. The key pieces of information here are the ConnectorID, SubscriptionID, and telemetry information.

- The next session capture shows the process received back the XML response below. The key pieces of content relevant here are within the SignalingListenerEndpointSettings section.. Interesting pieces of information here are:

- Name – his-nam1-eus1/TENANTID_CONNECTORID

- Namespace – his-nam1-eus1

- ServicePath – TENANTID_UNIQUEIDENTIFIER

- SharedAccessKey

This information is used by the MS AAD Application Proxy to establish listeners to two separate service endpoints at the Azure Service Bus. The proxy uses the SharedAccessKeys to authenticate to authenticate to the endpoints. It will eventually use the relay service offered by the Azure Service Bus.

- WireShark captured the DNS queries below resolving the IP for the service bus endpoint provided above. This query is performed twice in order to set up the two separate tunnels to receive relays.DNS Query for his-nam1-eus1.servicebus.windows.net

DNS Response with CNAME of ns-sb2-prod-bl3-009.cloudapp.net

DNS Response with IPDNS Query for his-nam1-eus1.servicebus.windows.net

DNS Response with CNAME of ns-sb2-prod-dm2-009.cloudapp.net

DNS Response with different IP - The MS AAD Application Proxy establishes connections with the two IPs received from above. These connections are established to port 5671. These two connections establish the MS AAD Application Proxy as a listener service with the Azure Service Bus to consume the relay services.

- At this point the MS AAD Application Proxy has connected to the Azure Service Bus to the his-nam1-cus1 namespace as a listener and is in the listen state. It’s prepared to receive requests from Azure AD (the sender), for verifications of authentication. We’ll cover this conversation a bit in the next few steps.When a synchronized user in the journeyofthegeek.com tenant accesses the Azure login screen and plugs in a set of credentials, Azure AD (the sender) connects to the relay and submits the authentication request. Like the initial MS AAD Application Proxy connection to the Azure Relay service, I was unable to capture the transactions in Fiddler. However, I was able to some of the conversation with API Monitor.

I pieced this conversation together by reviewing API calls to the ncryptsslp.dll and looking at the output for the BCryptDecrypt method and input for the BCryptEncrypt method. While the data is ugly and the listeners have already been setup, we’re able to observe some of the conversation that occurs when the sender (Azure AD) sends messages to the listener (MS AAD Application Proxy) via the service (Azure Relay). Based upon what I was able to decrypt, it seems like one-way asynchronous communication where the MS AAD Application Proxy listens receives messages from Azure AD.

- The LogonUserW method is called from CLR.DLL and the user’s user account name, domain, and password is plugged. Upon a successful return and the authentication is valided, the MS AAD Application Proxy initiates an HTTP POST to

his-eus-1.connector.his.msappproxy.net:10101/subscriber/connection?requestId=UNIQUEREQUESTID. The post contains a base64 encoded JWT with the information below. Unfortunately I was unable to decode the bytestream, so I can only guess what’s contained in there.{“JsonBytes”:[bytestream],”PrimarySignature”:[bytestream],”SecondarySignature”:null}

So what did we learn? Well we know that the Azure AD Pass-through authentication uses multiple Microsoft components including the MS AAD Application Proxy, Azure Service Bus (Relay), Azure AD, and Active Directory Domain Services. The authentication request is exchanged between Azure AD and the ApplicationProxyConnectorService.exe process running on the on-premises server via relay function of the Azure Service Bus.

The ApplicationProxyConnectorService.exe process authenticates to the URI where the bootstrap process occurs using a client certificate. After bootstrap the ApplicationProxyConnectorService.exe process obtains the shared access keys it will use to establish itself as a listener to the appropriate namespace in the Azure Relay. The process then establishes connection with the relay as a listener and waits for messages from Azure AD. When these messages are received, at the least the user’s password is encrypted with the public key of the client certificate (other data may be as well but I didn’t observe that).

When the messages are decrypted, the username, domain, and password is extracted and used to authenticate against AD DS. If the authentication is successful, a message is delivered back to Azure AD via the MS AAD Application Proxy service running in Azure.

Neato right? There are lots of moving parts behind this solution, but the finesse in which they’re integrated and executed make them practically invisible to the consumer. This is a solid out of the box solution and I can see why Microsoft markets in the way it does. I do have concerns that the solution is a bit of a black box and that companies leveraging it may not understand how troubleshoot issues that occur with it, but I guess that’s what Premier Services and Consulting Service is for right Microsoft? 🙂