This is part of my series on Azure Authorization.

- Azure Authorization – The Basics

- Azure Authorization – Azure RBAC Basics

- Azure Authorization – actions and notActions

- Azure Authorization – Resource Locks and Azure Policy denyActions

- Azure Authorization – Azure RBAC Delegation

- Azure Authorization – Azure ABAC (Attribute-based Access Control)

Welcome back fellow geeks.

I do a lot of learning and educational sessions with my customer base. The volume pretty much demands reusable content which means I gotta build decks and code samples… and worse maintain them. The maintenance piece typically consists of me mentally promising myself to update the content and kicking the can down the road for a few months. Eventually, I get around to updating the content.

This month I was doing some updates to my content around Azure Authorization and decided to spend a bit more time with Azure ABAC (Attribute-based access control). For those of you unfamiliar with Azure ABAC, well it’s no surprise because the use cases are so very limited as of today. Limited as the use cases are, it’s a worthwhile functionality to understand because Microsoft does use it in its products and you may have use cases where it makes sense.

The Dream of ABAC

Let’s first touch briefly on the differences between (RBAC) role-based access control and (ABAC) attribute-based access control. Attribute-based access control has been the dream for the security industry for as long as I can remember. RBAC has been the predominant authorization mechanism in a majority of applications over the years. The challenge with RBAC is it has typically translated to basic group membership where an application authorizes a user solely on whether or not the user is in a group. Access to these groups would typically come through some type of request for membership and implementation by a central governance team. Those processes have tended to be not super user friendly and the access has tended to be very course-grained.

ABAC meanwhile promised more fine-grained access based upon attributes of the security principal, resource, or whatever your mind can dream up. Sounds awesome right? Well it is, but it largely remained a dream in the mainstream world with a few attempts such as Windows Dynamic Access Control (Before you comment, yeah I get you may have had some cool apps doing this stuff years ago and that is awesome, but let’s stick with the majority). This began to change when cloud came around with the introduction of more modern protocols and standards such as SAML, OIDC, and OAuth. These protocols provide more flexibility with how the identity provider packages attributes about the user in the token delivered to the service provider/resource provider/what have you.

When it came to the Azure cloud, Microsoft went the traditional RBAC path for much of the platform. User or group gets placed in Azure RBAC role and user(s) gets access. I explain Azure RBAC in my other posts on RBAC. There is a bit of flexibility on the Entra ID side for the initial access token via Entra ID Conditional Access, but RBAC in the Azure realm. This was the story for many years of Azure.

In 2021 Microsoft decided something more flexible was needed and introduced Azure ABAC. The world rejoiced… right? Nah, not really. While the introduction of ABAC was awesome, its scope of use was and still is extremely limited. As of the date of this blog, ABAC is only usable for Azure Storage blob and queue operations. All is not lost though, there are some great use cases for this feature so it’s important to understand how it works.

How does ABAC work?

Alright, history lesson and complaining about limited scope aside, let’s now explore how the feature works.

ABAC is facilitated through an additional property on Azure RBAC Role Assignment resources. I’m going to assume you understand the ins and out of role assignments. If you don’t, check out my prior post on the topic. In its most simple sense, an Azure RBAC role assignment is the association of a role to a security principal granting that principal the permissions defined in the role over a particular scope of resources. As I’ve covered previously, role assignments are an Azure resource that have defined sets of properties. The properties we care about for the scope of this discussion are the conditionVersion and condition properties. The conditionVersion property will always have a value of 2.0 for now. The condition property is where we work our ABAC magic.

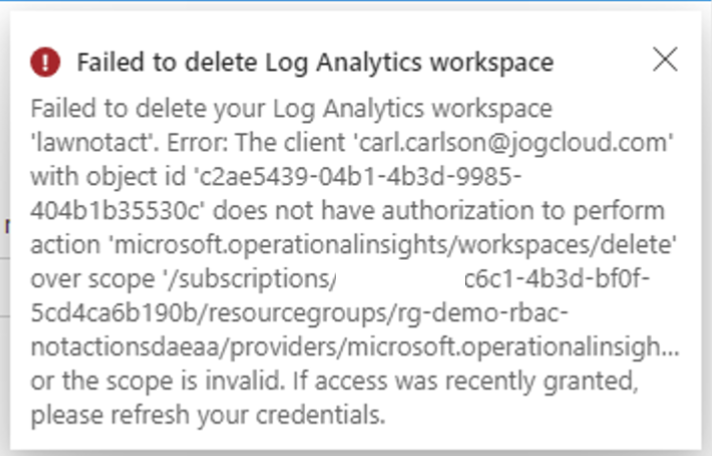

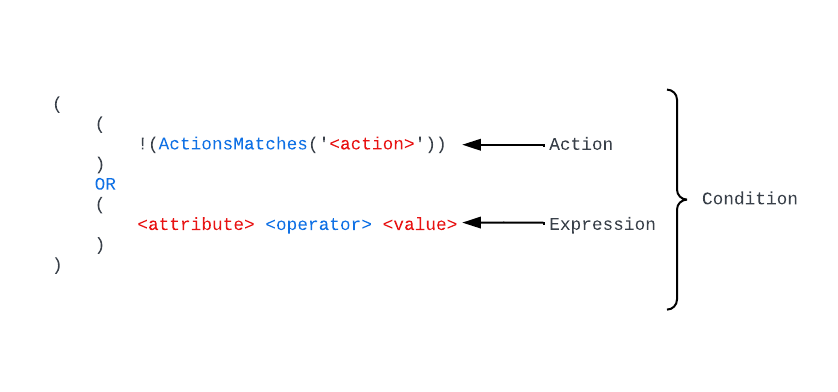

The condition property is made up of a series of conditions which each consist of an action and one or more expressions. The logic for conditions is kinda weird, so I’m walk you through it using some of the examples from documentation as well as complex condition I throw together. First, let’s look at the general structure.

In the above image you can see the basic building blocks of a condition. Looks super confusing and complicated right? I know it did to me at first. Thankfully, the kind souls who write the public documentation broke this down in a more friendly programming-like way.

In each condition property we first have the action line where the logic looks to see if the action being performed by the security principal doesn’t (note the exclamation point which negates whats in the parentheses) match the action we’re applying the conditions to. You’ll commonly see a line like:

!(ActionMatches{'Microsoft.Storage/storageAccounts/blobServices/containers/blobs/read'} AND !SubOperationMatches{'Blob.List'})This line is saying if the action isn’t blobs/read (which would be data plane call to read the contents of the blob) then the line should evaluate to true. If it evaluates to true, then the access is allowed and the expressions are not evaluated any further.

After this line we have the expression which is only evaluated when the first line evaluates to false (which in the example I just covered would mean the security principal is trying to read the content of a blob). The expressions support four categories of what Microsoft refers to as condition features. There are currently four features in various states of GA (general availability) and preview (refer to the documentation for those details). These four categories include:

- Requests

- Environment

- Resource

- Principal (security principal)

These four categories give you a ton of flexibility. Requests covers the details of the request to storage, for example such as limiting a user to specific blob prefixes based on the prefix within the request. Environment can be used to limit the user to accessing the resource from a specific Private Link Private Endpoint over Private Link in general (think defense-in-depth here). The resource feature exposes properties of the resource being accessed, which I find the most flexible thing to be blob index tags. Lastly, we have security principal and this is where you can muck around with custom security attributes in Entra ID (very cool feature if you haven’t touched it).

In a given condition we can have multiple expressions and within the condition property we can string together multiple conditions with AND and OR logic. I’m a big believer in going big or going home, so let’s take a look at a complex condition.

Diving into the Deep End

Let’s say I have a whole bunch of data I need to make available via a blobs in an Azure Storage Account. I have a strict requirement to use a single storage account and the blobs I’m going to store have different data classifications denoted by a blob index tag key named access_level. Blobs without this key are accessible by everyone while blobs classified high, medium, or low are only accessible by users with approval for the same or higher access levels (example: user with high access level can access high, medium, low, and data with no access level). Lastly, I have a requirement that data at the high access level can only be accessed during business hours.

I use a custom security attribute in Entra ID called accesslevel under an attribute set named organization to denote a user’s approved access level.

Here is how that policy would break down.

My first condition is built to allow users to read any blobs that don’t have the access_level tag.

# Condition that allows users within scope of the assignment access to documents that do not have an access level tag

(

(

# If the action being performed doesn't match blobs/read then result in true and allow access

!(ActionMatches{'Microsoft.Storage/storageAccounts/blobServices/containers/blobs/read'} AND !SubOperationMatches{'Blob.List'})

)

OR

(

# If the blob doesn't have a blob index tag with a key of access_level then allow access

NOT @Resource[Microsoft.Storage/storageAccounts/blobServices/containers/blobs/tags&$keys$&] ForAnyOfAnyValues:StringEquals {'access_level'}

)

)

If the blob does have an access tag, I want to start incorporating my logic. The next condition I include allows users with the accesslevel security attribute set to high to read blobs with a blob index tag of access_level equal to low or medium. I also also allow them to read blobs tagged with high if it’s between 9AM and 5PM EST.

# Condition that allows users within scope of the assignment to access medium and low tagged data if they have a custom

# security attribute of accesslevel set to high. High data can also be read within working hours

OR

(

(

# If the action being performed doesn't match blobs/read then result in true and allow access

!(ActionMatches{'Microsoft.Storage/storageAccounts/blobServices/containers/blobs/read'} AND !SubOperationMatches{'Blob.List'})

)

OR

(

# If the blob has an index tag of access_level with a value of medium or low allow the user access if they have a custom security

# attribute of organization_accesslevel set to high

@Resource[Microsoft.Storage/storageAccounts/blobServices/containers/blobs/tags:access_level<$key_case_sensitive$>] ForAnyOfAnyValues:StringEquals {'medium', 'low'}

AND

@Principal[Microsoft.Directory/CustomSecurityAttributes/Id:organization_accesslevel] StringEquals 'high'

)

OR

(

# If the blob has an index tag of access_level with a value of high allow the user access if they have a custom security

# attribute of organization_accesslevel set to high and it's within working hours

@Resource[Microsoft.Storage/storageAccounts/blobServices/containers/blobs/tags:access_level<$key_case_sensitive$>] ForAnyOfAnyValues:StringEquals {'high'}

AND

@Principal[Microsoft.Directory/CustomSecurityAttributes/Id:organization_accesslevel] StringEquals 'high'

AND

@Environment[UtcNow] DateTimeGreaterThan '2025-06-09T12:00:00.0Z'

AND

@Environment[UtcNow] DateTimeLessThan '2045-06-09T21:00:00.0Z'

)

)Next up is users with medium access level. These users are granted access to data tagged medium or low.

# Condition that allows users within scope of the assignment to access medium and low tagged data if they have a custom

# security attribute of accesslevel set to medium

OR

(

(

# If the action being performed doesn't match blobs/read then result in true and allow access

!(ActionMatches{'Microsoft.Storage/storageAccounts/blobServices/containers/blobs/read'} AND !SubOperationMatches{'Blob.List'})

)

OR

(

# If the blob has an index tag of access_level with a value of medium or low allow the user access if they have a custom security

# attribute of organization_accesslevel set to medium

@Resource[Microsoft.Storage/storageAccounts/blobServices/containers/blobs/tags:access_level<$key_case_sensitive$>] ForAnyOfAnyValues:StringEquals {'medium', 'low'}

AND

@Principal[Microsoft.Directory/CustomSecurityAttributes/Id:organization_accesslevel] StringEquals 'medium'

)

)Finally, I allow users with low access level to access data tagged as low.

# Condition that allows users within scope of the assignment to access low tagged data if they have a custom

# security attribute of accesslevel set to low

OR

(

(

# If the action being performed doesn't match blobs/read then result in true and allow access

!(ActionMatches{'Microsoft.Storage/storageAccounts/blobServices/containers/blobs/read'} AND !SubOperationMatches{'Blob.List'})

)

OR

(

# If the blob has an index tag of access_level with a value of low allow the user access if they have a custom security

# attribute of organization_accesslevel set to low

@Resource[Microsoft.Storage/storageAccounts/blobServices/containers/blobs/tags:access_level<$key_case_sensitive$>] ForAnyOfAnyValues:StringEquals {'low'}

AND

@Principal[Microsoft.Directory/CustomSecurityAttributes/Id:organization_accesslevel] StringEquals 'low'

)

)Notice how I separated each condition using OR. If the first condition resolves to false, then the next condition is evaluated until all access is granted or all conditions are exhausted. Neat right?

Summing it up

So why should you care about this if its use case is so limited? Well, you should care because that is ABAC’s use case today, and it would be expanded in the future. Furthermore, ABAC allows you to be more granular in how you grant access to data in Azure Storage (again, blob or queue only). You likely have use cases where this can provide another layer of security to further constrain a security principal’s access. You’ll also see these conditions used in Microsoft’s products such as AI Foundry.

The other reason it’s helpful to understand this language used for the condition, is conditions are expanding into other services such as Azure RBAC Delegation (which if you aren’t using you should be). While the language can be complex, it does make sense if you muck around with it a bit.

A final bit of guidance here, don’t try to write conditions by hand. Use the visual builder in the Azure Portal as seen below. It will help you get some basic conditions in place that you can further modify directly via the code view.

Next time you’re locking down an Azure storage account, think about whether or not you can further restrict humans and non-humans alike based on the attributes discussed today. The main places I’ve seen this used are for user profiles, further restricting user access to specific subsets of data (similar to the one I walked through above), or even adding an additional layer of network security baked directly into the role assignment itself.

See you next post!